Researched by Robyn Jensen & Rich Necker. Written by Robyn Jensen

Born: January 16, 1906, in Benton, Alabama

Died: April 28th, 1962, in Jacksonville, Florida

Career: 1933 to 1959 (Puerto Rico & Cuban Winter Leagues, Negro Leagues, Canada) Positions: 1b, Outfielder, Manager

Bats Right, Throw Right Height: 6’1 Weight: 200 lbs

Prologue: In October, I had put out a call for help in finding out what happened to Big Jim Williams, who had an impressive career in the Negro Leagues before coming to Canada in the 1950s. After five summers in Saskatchewan, he returned to the United States, and I hit a wall. I tried to find where he ended up. That is, until a brief mention in the papers in 1959, he vanished again. No one knew when and how he died. Rich Necker, baseball co-researcher extraordinaire of attheplate.com, took up the torch to help me solve what happened to Big Jim and fill in the blanks from 1955 to 1959– thank you, Rich!

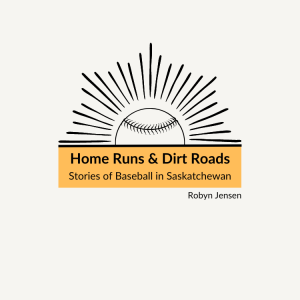

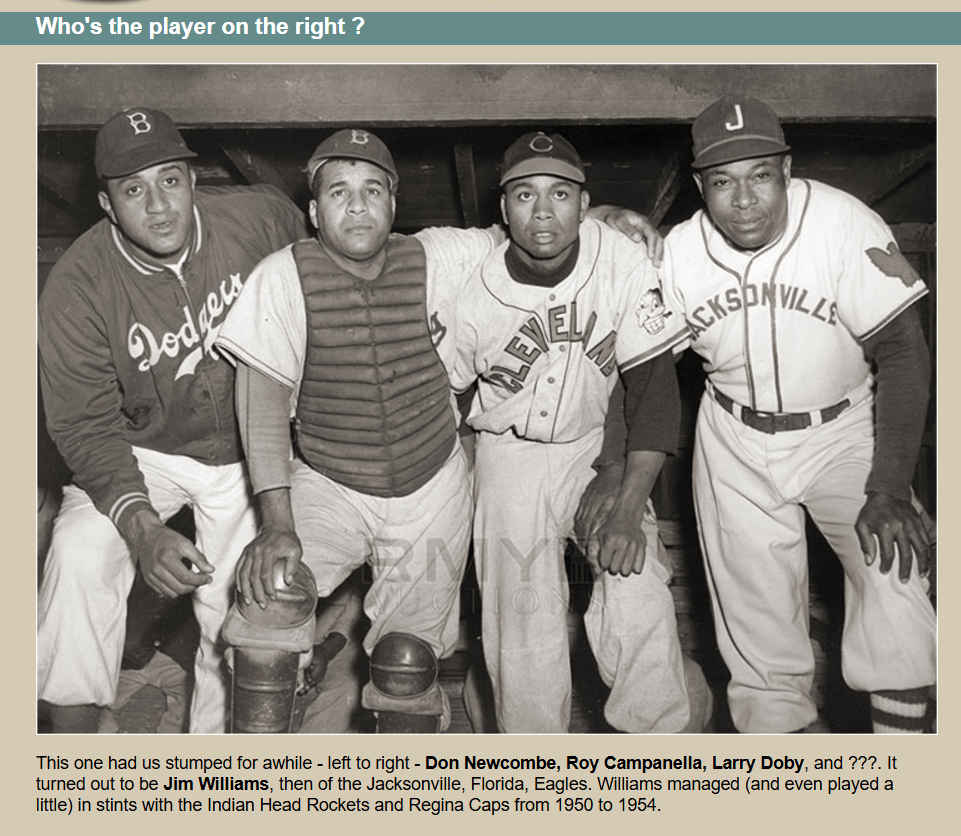

While the journey to uncover the story of Big Jim Williams has led to an unfortunate closure, it has served as a poignant reminder of the struggles faced by African American men during an era of profound racial injustice. Our search for his story is a small act of recognition—of giving voice to the men who, despite the obstacles, helped shape the game of baseball. He is important to our history as the manager of the Indian Head Rockets from 1950 to 1952, as well as a player. This included a farewell stint with the club during the latter portion of the 1954 campaign when he was signed by the organization in the role of a pinch-hitting specialist.

The quest to find his story continues to shed light on forgotten and often silenced ball players. Like many others, his memory is kept alive through our efforts as storytellers, reminding us that no one’s story is truly lost as long as we keep seeking it.

Big Jim’s Early Years

James Riley, author of The Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Leagues, describes James ‘Big Jim’ Williams as a young outfielder: “Big, strong and fast, he could run, hit and hit with power, but his fielding was unexceptional, and his throwing arm was a bit lacking.” (pg. 852) He was known for his aggressive playstyle and sometimes dirty antics, earning mixed reviews from peers.

His career included stints with prominent teams such as the New York Black Yankees, Newark Eagles, Homestead Grays, and the Cleveland Bears. Williams achieved notable success with the Homestead Grays in the late 1930s, playing outfielder and hitting with a .363 average behind Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard, contributing to their dominance. He moved over to the Toledo Crawfords in the Negro American League. Under the manager Oscar Charleston, his performance in 1939 earned him a spot in the prestigious East-West All-Star Game.

Source: Edmonton Journal, 11 Jun 1951, Pg.11

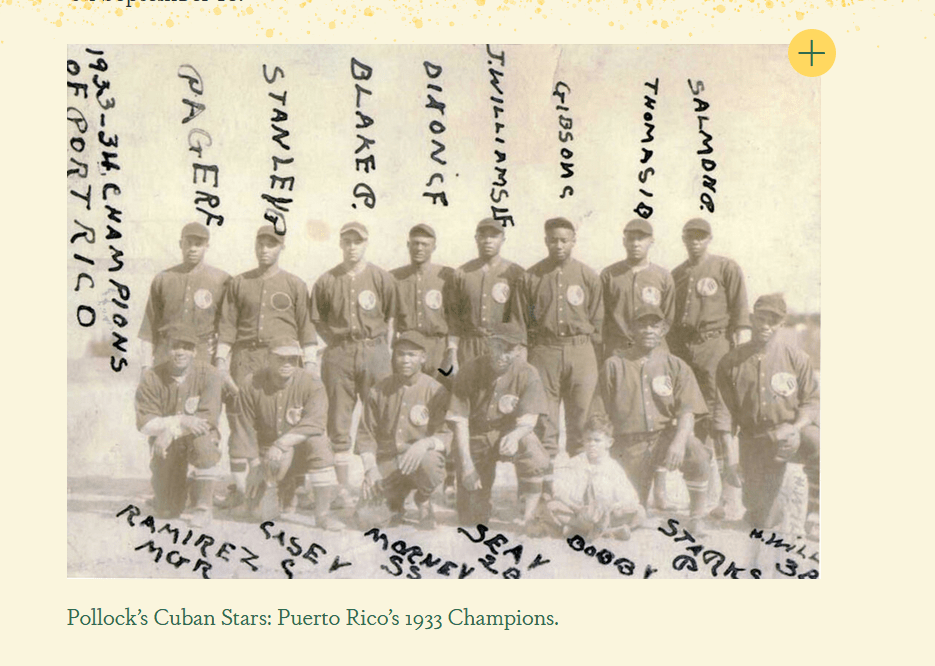

During the 1930s, Williams also went to Puerto Rico and played in their winter leagues. He was part of the 1933 Champion team, the Pollock’s Cuban Stars.

Back row (L to R) Theodore Page RF, John Stanley P, (first name unknown) Blake P, Herbert Dixon CF, James Williams LF, Joshua Gibson C, David Thomas 1B, Harry Salmon P

Front row (L to R) Ramiro Ramirez MGR, William Casey C, Leroy Morney SS, Richard Seay 2B, Otis Starks P, Harry Williams 3B

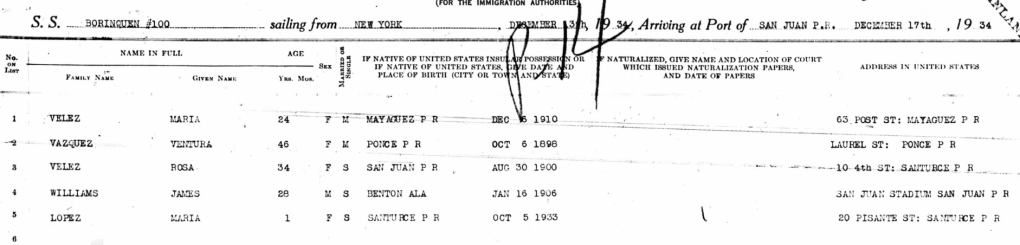

Here is the Passenger List carrying 13 of the 14 players- SS Carabobo – LV New York Nov. 15/33 ARR San Juan PR Nov. 20/33:

The ship manifestos are a great way to track where ball players travelled to in the Winter seasons. This one indicates that Williams, in 1934 went to Puerto Rico:

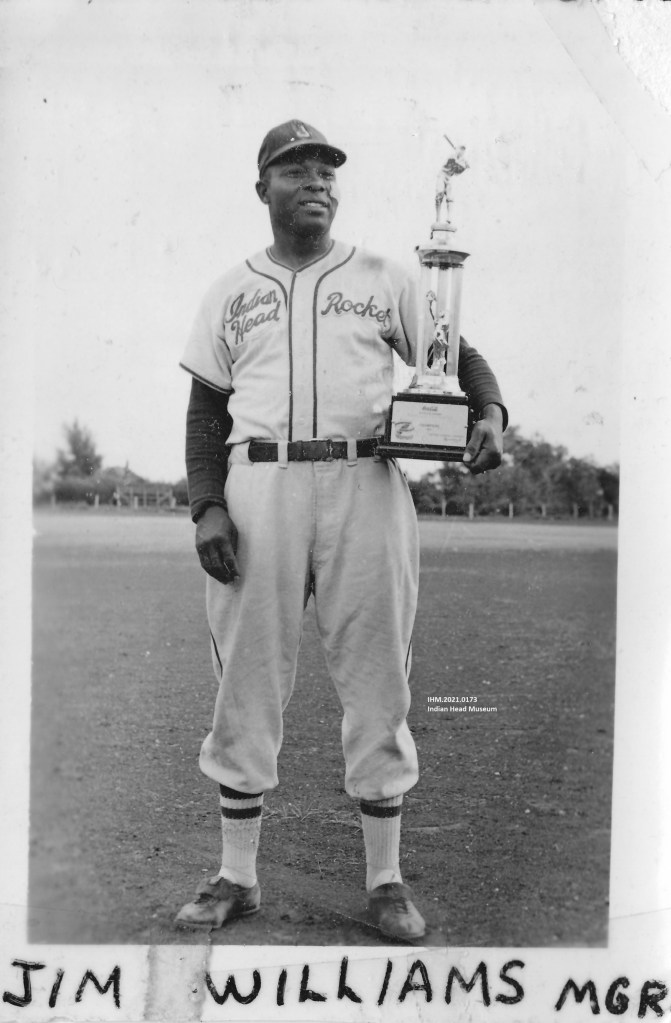

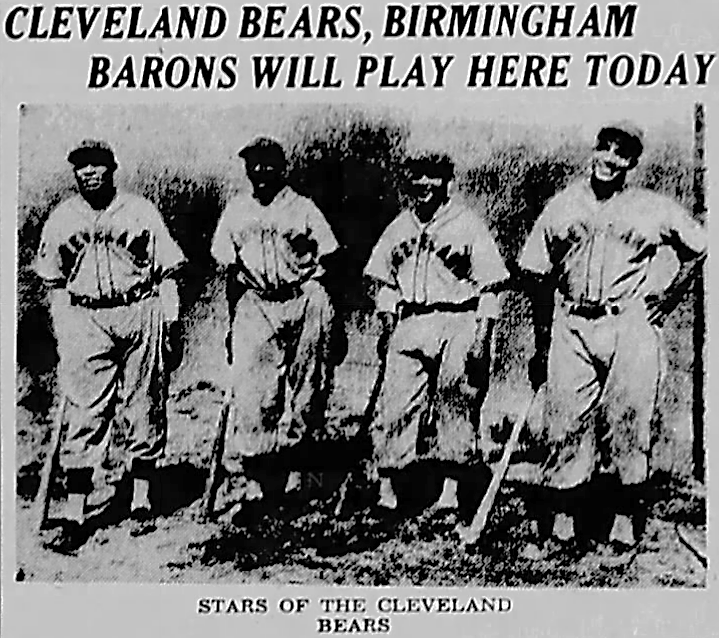

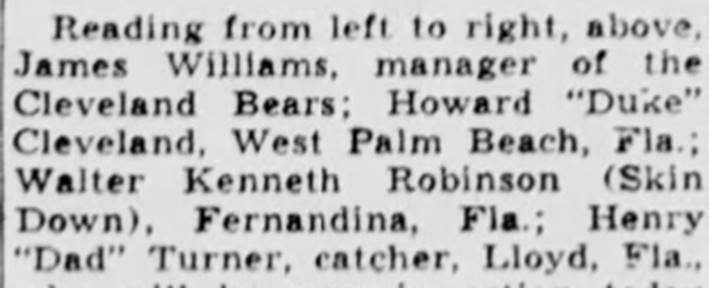

In 1940, he left the Crawfords to take the managerial reins of the Cleveland Bears, as played by the Jacksonville Red Caps.

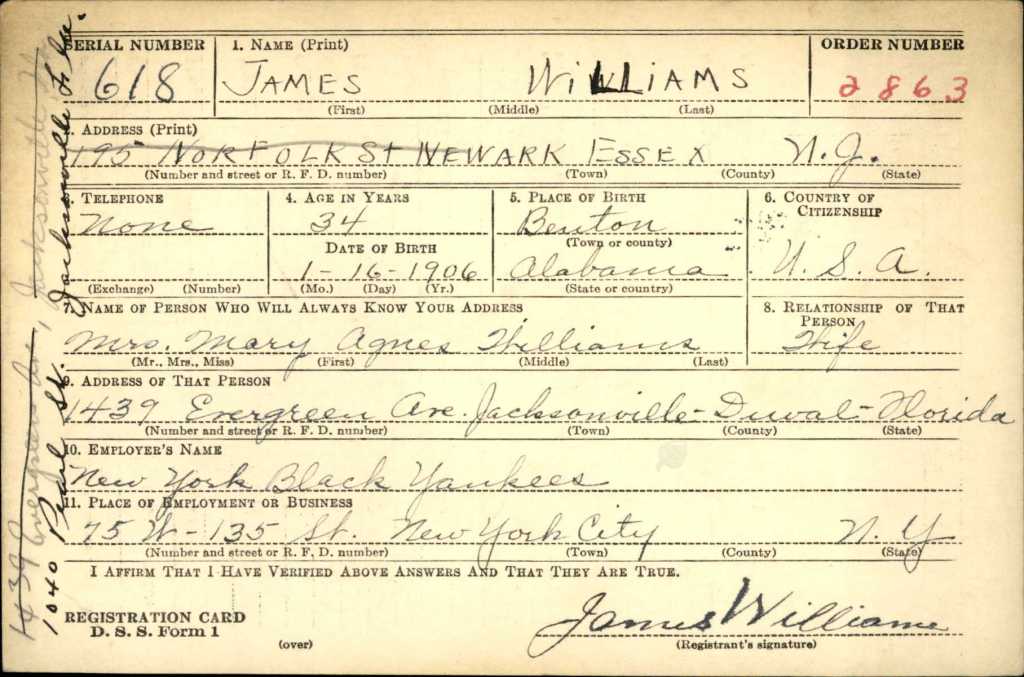

Williams also registered for the military draft in 1940, but his name was never drawn in the lottery process, and he never served in WW2. The record shows he was married, and before the season was over, the draft card indicates he shifted from the Crawfords to the New York Black Yankees. The 34-year-old right-fielder stats by Riley indicate that he ended his season with “uncharacteristically low averages of .200 and .245”

Williams, keeping his feet in both worlds, became the player/manager for the Durham Eagles for a couple of years before moving some of his best players to the Jacksonville Eagles. He seemed to be slipping out of the limelight, but by 1950, a new chapter had arrived- Big Jim in Canada. Far removed from the publicity of the Negro Leagues, his larger-than-life presence would both challenge the patience of league officials and elevate the level of competition, propelling Saskatchewan’s baseball scene to new heights.

Canada Bound

It was a call-out from a town of about 1,200 residents called Indian Head in Saskatchewan, Canada, some 3551 km (33-hour bus ride) north of his home base in Jacksonville, Florida. After years of hosting successful baseball tournaments, Indian Head was ready for a team to represent the community in league and exhibition play. With a keen eye on the talent level of American barnstorming teams, the community’s interest zeroed in on teams across the border. With Mayor Jimmy Robison at the helm, a small delegation headed to Wichita, Kansas, to speak with National Baseball Congress founder Ray “Hap” Dumont. It’s unclear who recommended the Jacksonville Eagles to Robison after initial conversations were directed at finding a team through a contact in Milwaukee. It seems something fell through, and as fate has it, more discussions were had, and a deal was struck with Eagles owner Cutprice Washington to hire the team for the summer to play as The Indian Head Rockets.

Williams accompanied the team as the player/manager from 1950 to 1952. And, as destiny would have it, he was in Saskatchewan during July 1954 when the Rockets’ player roster was depleted and answered the call to re-join the team, on this occasion solely as a player, ending his playing career as a vital pinch-hitter who was sent to the plate in critical late-inning situations when a big hit was needed.

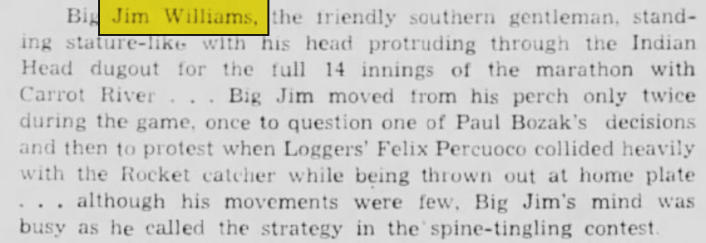

Early impressions of Big Jim by the media were favourable:

In Black Baseball Player in Canada – A Biographical Dictionary 1881-1960, authors Jay-Dell Mah and Barry Swanton provide Williams’ highlights:

“In 1951, he managed The Rockets to a 33-12 first place record and the Saskatchewan semi-pro title. His team featured a 22-game winning streak. June 4th, 1951, Williams belted a pair of homers as Indian Head swept a four-game weekend series at Delisle and North Battleford. July 31st, Williams was suspended for six games and fined $50 for assaulting an umpire on a street in Medicine Hat. The attack occurred following the first game of the doubleheader against the hometown Mohawks. It was in the aftermath of a ninth-inning rhubarb when Williams disputed a called strike by Umpire E. C. Terry and was ordered to leave the ballpark. When Williams refused to leave, the game was forfeited to the Hawks. A short time later, Terry said he was walking down the street away from the park when The Rockets’ bus pulled up and Williams got out and crossed the street where he used violent language and threw a punch at Terry. August 22, Williams had a double and two singles as Indian Head evened a play-off series with Moose Jaw with a 6-2 victory.”

Enlargement of Indian Head Museum photo (IHM.2021.0173)

In a 2012 interview with the Leader-Post, Rockets second baseman Willie Reed recalled he and his teammates referring to Williams as a “muscle jaw” because he clenched his teeth when he talked. Here is Williams in the ’52 team photo:

No matter how challenging the circumstances were, Williams seemed to keep his word by any means possible:

In 1953, big Jim moved over to the Regina Caps:

“June 21, 1953, the president of the Canadian Western Baseball League announced Williams had been fined $25 and suspended for 14 games as a result of a rhubarb in a game in Saskatoon June 14. Williams was reported to have struck umpire Bill Sawusch of Chicago. Aug 8, in the lineup because of injuries to three of his key players, Williams had a double and a single in drove in a run. Three days later, he was even better with a double and two singles, driving in three runs. Aug 12, Williams had a three run homer and the following day he had a double and two singles.” (In Black Baseball Player in Canada, Mah and Swanton)

The 14-game suspension equates to close to 29% of 49 Saskatchewan Baseball League games:

In his last year in Canada, he returned with a barnstorming team called the Florida Eagles. Rich Necker shares:

“Aside from the Kamsack tournament mentioned in the clip, the touring Florida Eagles had only a brief stay in Saskatchewan and were known to have played in the Indian Head tournament (a 12 – 4 loss to the Rockets) plus two games in the Shaunavon tourney (a win over Shaunavon and a defeat against the Moose Jaw Lakers). Big Jim even wound up playing a few games for the 1954 Rockets (managed by Gilberto Yzquierdo) late in the campaign when the organization was drowning in debt and had to bring in a few replacement players after the team had released a number of their original team roster.”

Back to the Negro Leagues from 1955 to 1959

Williams headed back to Florida to coach for the Jacksonville Eagles. With Big Jim at the helm, newspapers praise his victories over teams such as the Birmingham Black Barons, the Baltimore Elite Giants, and the Martinville All-Stars.

Sources: Charlotte NC Observer, April 21, 1955 & Kannapolis NC Daily Independent, April 16, 1955

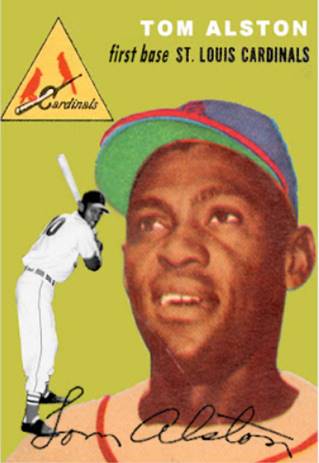

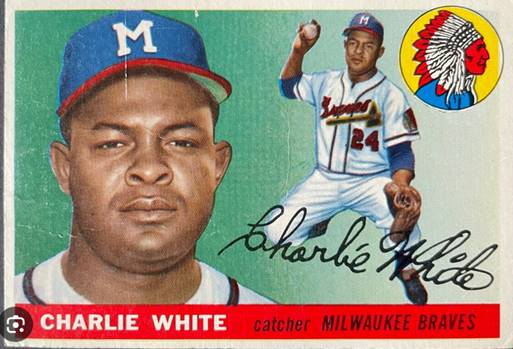

The Kannapolis article credits Big Jim with mentoring two players who hit the major leagues—Tom Alston of the St. Louis Cardinals and Charlie White of the Milwaukee Braves. Williams, who did not reach MLB status during his life, must have been proud to see two of his players succeed. The article also boosts Williams’ coaching success of four pennants and 36 tournament titles.

Sources: Durham NC Herald-Sun May 4, 1956 & Florida Star, May 11, 1957

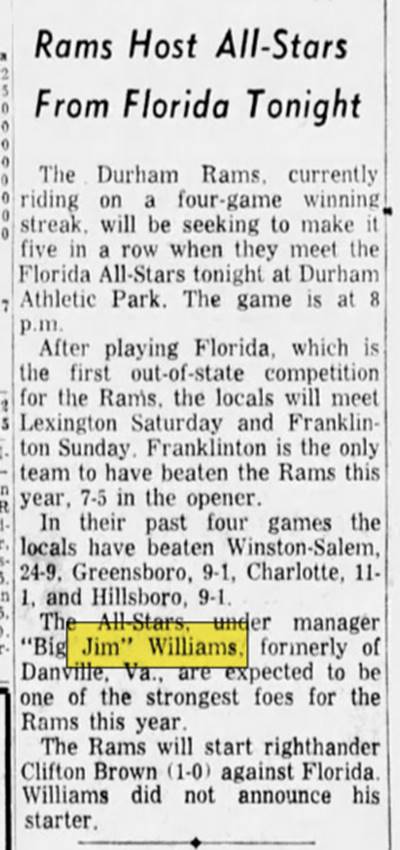

In 1956, Williams moved to the Florida All-Stars and referenced a former team (Danville All-Stars) in Danville, Virginia.

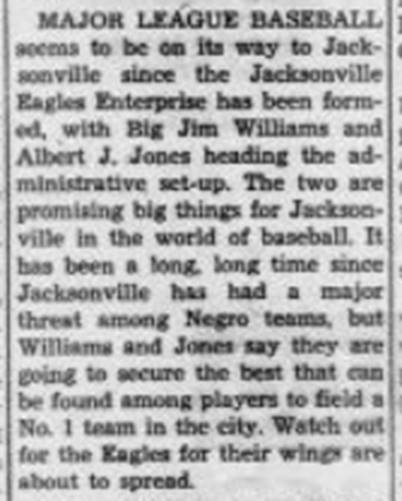

By 1957, Williams, confident and thriving, was looking to apply for an expansion franchise for Jacksonville within the lone remaining major league for African Americans, the failing Negro American League (which was on its last legs but would endure until 1960 before disbanding). Along with his partner, who is identified as Albert J. Jones, “Big Jim” was hopeful that this new endeavor would be prosperous financially and offer new opportunities for upcoming African-American ball players within the framework of a segregated league. All this, at a time when the integration of previously-segregated players into organized baseball was gradually proceeding while, ironically, ownership opportunities for African-American entrepreneurs in baseball was slipping away.

During the years Big Jim Williams spent in Canada, he showcased both the heights of his baseball prowess and the unrelenting fire that defined his character—his time as a player and manager in Saskatchewan left a lasting impact, elevating the competitive spirit of the leagues and etching his name into the province’s baseball lore. However, his clashes with authority and the turbulent circumstances surrounding his career hinted at the challenges ahead. As he returned to the United States to continue his baseball journey, the successes he found on the field would soon give way to a darker and more tragic chapter.

Big Jim’s Life Takes an Unfortunate Turn

Newspaper Headline: “Jim” Williams Get 4 Months

Florida Star, August 5th, 1961

“A two-year bribery case ended in criminal court on Thursday, July 27th, when James Williams, former deputy constable, received a four-month term in county jail on a misdemeanor charge of bribery. Williams, 49 [He was actually 55], a former outfielder with the New York [Black] Yankees, reportedly was involved in the shakedown of a burglary suspect, Freddie Patton, when he was apprehended.

The former officer stood to receive 10 years of the conviction, which had been brought back as a felony. But Court Judge A. Lloyd Layton had granted a defense motion for a new trial on the grounds that the Florida Supreme Court had defined actions such as those of Williams as malpractice in the office rather than grand larceny.

On July 31st, 1959, Williams reputedly accepted $200 from Freddie Patton on the corner of Beaver and Jefferson. Patten had borrowed the money from an employer, Roy Leite, who called the country solicitor’s office to report the matter.

Patten was given marked bills for the payoff. When Williams received the money, he allegedly went to Judge Sarah Bryan’s office, where he was arrested. Williams admitted that he had taken the money from Patten and said he was going to help dispose of the pending case against Patten. He was going to see the complainants of the pending case and ask if they wanted any part of the $200 he had taken Patten not to appear against him. The prosecution of Williams was termed one of the most tedious annals of the local court.”

My thoughts

In 1959, Williams became a deputy constable with the Jacksonville police department assigned to patrol the ‘Negro Block.’ This news article outlines Big Jim’s downfall in the force. However, if reading between the lines, this case widens the scope of Florida’s complex interplay of race, authority, and justice during the late 1950s and early 1960s. As an African American man and a former law enforcement officer, Williams occupied a precarious position in a society marked by systemic racism and segregation. As you read through, you can see how it was handled and pursued with extraordinary vigor and involving an elaborate sting operation. This suggests a level of scrutiny that may not have been applied to a white counterpart in the same position. Although his charges were ultimately reduced and his sentence lightened, the process underscored the unequal treatment African American individuals often faced within the legal system, particularly when accused of misconduct in roles of authority. The language used to describe his prosecution and the initial severity of the charges reflect broader societal biases. At the same time, the damage to his reputation as a public figure illustrates the lasting consequences of these systemic inequities. Reading Williams’ case today serves as a poignant reminder of the racialized disparities that shaped—and, in many ways, continue to shape—the American justice system.

The intense public scrutiny and humiliation surrounding the case may have contributed to the dissolution of Big Jim Williams’ marriage to Mary Agnes in January 1962. Following his dismissal, he could only secure work as a bouncer at a local establishment called Weaver’s Pine Inn. Tragically, on April 28, 1962, Williams approached two patrons in response to gunshots heard in the back alley and asked them to check their weapon. The patrons turned their gun on him and opened fire, leading to his untimely death.

Wilson (A White Man) comes to Williams’ Defense.

Newspaper Headline: The Truth About My Dismissed by Dick (Baldy) Wilson

Florida Star, May 26th, 1962 (One month after Big Jim’s death)

“I am aware that for the past several months since my release from Constable’s office, there has been wide speculation as to the circumstances behind my ‘firing”.

Let me add a point here that somewhat saddens me. It has to do with Jim Willaims, a former deputy constable, who in his lifetime had been known affectionately as “Big Jim.”

It is generally known among leading Negro ministers in this town that Jim Williams had openly and repeatedly stated how Constable Hutchins had enticed him by offering him a job to dig up some incriminating facts on me in order that could dismiss me. Jim told this to many people before he met with his recent untimely death.

If anyone were to question my former boss, Constable Douglas Hutchins (who was a Farris Bryant appointee and a political unknown before the death of the former constable) he would no doubt create several reasons for my dismissal. The ones he seems, however, are my on-duty and off-duty social associations and something which he describes as “conduct unwelcoming an officer.”

Despite Mr. Hutchins’ propaganda, it is known to many people that my dismissal was a matter of political expediency rather than my personal behavior as a law officer. My successor was handpicked by members of the Negro ‘block’ in this city….”

My thoughts #2

Dick Wilson’s defense of Big Jim in the aftermath of his death adds another layer to the racial and political dynamics surrounding Williams’ case. It sheds light on the systemic pressures he faced. Wilson’s account suggests that Williams was coerced into targeting Wilson himself, with the promise of professional security in exchange for incriminating evidence. This paints Williams not merely as a man accused of misconduct but as someone potentially manipulated by those in power to serve their political and personal agendas. Wilson’s revelation that Williams openly spoke about these pressures before his death reinforces the notion that Williams’ actions cannot be entirely removed from the racialized and politicized environment of the time.

The involvement of Constable Hutchins, a white appointee of Governor Farris Bryant, underscores the intersection of race and politics. Hutchins’ alleged manipulation of Williams to achieve political goals highlights the exploitative dynamics African American officers could face, where their positions of authority were contingent on serving the interests of white superiors. Wilson’s dismissal and replacement with a figure chosen by the “Negro block” add further complexity, suggesting a contentious relationship between African American political leadership and individual African American officers, with race being weaponized for political expediency.

Wilson’s critique of Hutchins’ vague reasons for his dismissal—social associations and “conduct unbecoming an officer”—further illustrates the ambiguity often used to justify actions against African American professionals. This ambiguity not only obscures the truth but also reinforces racial stereotypes and delegitimizes their roles. Wilson’s decision to speak out about Williams’ coerced involvement and his dismissal provides a rare glimpse into the internal power struggles within law enforcement during this era, where race, politics, and professional survival were deeply intertwined.

Ultimately, Wilson’s defense reframes Jim Williams as a man caught in a web of systemic racism and political machinations, complicating the narrative of his bribery conviction. It suggests that Williams’ case cannot be fully understood without recognizing the broader structural forces that shaped his decisions and, ultimately, his downfall.

‘Big Jim’ Loved Baseball Until The End

Baseball was a cornerstone of Big Jim Williams’ life, providing purpose amid his challenges. As a star outfielder for many Negro Leagues, Williams showcased his talent and passion for the game, which remained central to his identity even after his playing career ended. Transitioning to managing, he led the Jacksonville Eagles, a former Class-A team, guiding them to compete across the U.S. and Canada. He took great pride in mentoring his ball players, and two of them, Tom Alston and Charlie White, went on to the major leagues. This connection to baseball offered him a sense of accomplishment and community, even as his life became controversial as a deputy constable.

Amid the legal troubles, public scrutiny, and eventual dismissal from his position, baseball remained a steady and meaningful presence—Big Jim truly loved baseball. Tragically, this passion was severed by his untimely death in April 1962, when he was killed while working as a bouncer. Despite the challenges and injustices, he endured, Williams’ dedication to baseball highlights how the sport not only defined his public legacy but also provided him with a sense of stability and belonging during turbulent times.

Williams brought with him the skills and professionalism he learned in the Negro Leagues, elevating the level of play in local leagues. His presence on Saskatchewan teams contributed to their success and enriched the province’s cultural and sporting landscape.

For Williams, playing in Saskatchewan offered an opportunity to escape the overt racial discrimination of the Jim Crow South. While not entirely free from prejudice, Canada afforded him more respect and freedom to showcase his talents. This experience likely deepened his connection to the game as a source of empowerment and pride.

Williams’ legacy in Saskatchewan and Indian Head extends beyond his performance on the field. For a short time, he was part of our community, and we know that Big Jim felt a sense of belonging and acceptance in Canada. Here, as “muscle jaw,” Williams left his mark on our local sports history and contributed to the province’s rich baseball heritage.

Epilogue: What next? I hope to find Big Jim’s grave and work with the Negro Leagues Baseball Grave Marker Project of the Negro Leagues Committee of SABR, which strives to provide proper grave markers for players of the Negro Leagues to honor their contributions to history and the game of baseball. Wish me luck!