Introduction

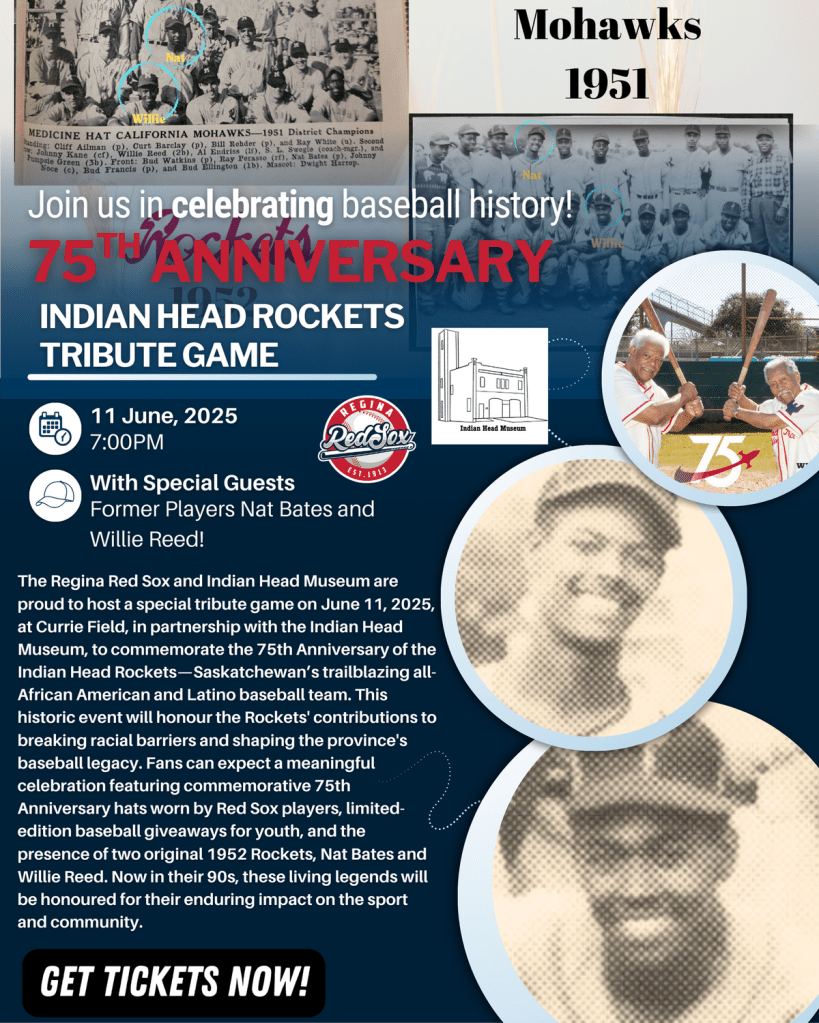

On June 11, 2025, a packed crowd at Regina’s Currie Field rose to its feet as two nonagenarians, Nat Bates and Willie Reed, stepped onto the diamond. They weren’t just guests of honour; they were history in motion. Seventy-three years earlier, the two had suited up for the Indian Head Rockets, Saskatchewan’s first African American and Latino professional baseball team. Now, they had returned for a tribute game that celebrated not only their legacy, but the long, often overlooked story of how players of African descent came to shape baseball on the Canadian prairie.

Their presence was a powerful reminder that Saskatchewan’s baseball history is far richer than box scores and standings. Beginning as early as the 1920s, African descent athletes from the United States found opportunities to play in communities across the province, thanks in large part to outlaw leagues that defied segregationist norms. This tribute game was more than a commemorative event; it was a living acknowledgment of that legacy. To understand how we arrived at that moment, how prairie towns once hesitant to embrace racial diversity came to celebrate it so openly, we must look back at the early chapters of this remarkable and unlikely journey.

How Players of African Descent Came to Saskatchewan

As early as the 1920s, Saskatchewan baseball clubs began recruiting African American players from the United States. John Donaldson, a pitching sensation and one of the most celebrated Black players of his era, was recruited by Moose Jaw in 1926. (attheplate.com) By the 1930s, teams like the Broadview Buffaloes were fielding multiple African American players—up to five between 1935 and 1937 (Hack, Shury, & Committee, 1997, p. 117).

This shift raised questions, especially in light of the treatment of players like Dick Brookins, an African American ballplayer who was deported from Canada just 25 years earlier for trying to play professionally. (Necker, n.d.-b) How, then, were rural Saskatchewan teams suddenly importing Black talent despite widespread racial exclusion in organized baseball?

The answer lies in the rise of “outlaw baseball.” As historians Jay-Dell Mah and Rich Necker explain, most Saskatchewan leagues by the 1930s operated outside the formal structure of organized baseball, free from the rules and restrictions imposed by Major League Baseball and its provincial amateur counterparts. These independent, or “outlaw,” leagues were not bound by the unwritten rules that barred African American players, and thus had the freedom to recruit talent based purely on skill and spectacle (Mah & Necker, 2023).

Many of these players were already well known on the North American barnstorming circuits. There were teams like the Ligon All-Stars, Kansas City Monarchs, Gilkerson’s Colored Giants, and the famed Satchel Paige’s squads. The teams toured through Canada, dazzling fans with their charisma and play (Hack, Shury, & Committee, 1997, p. 151). Their exposure sparked a shift in local attitudes. Prairie teams began actively looking south to bolster their rosters, knowing that adding African American players could offer a crucial competitive edge (Swanton, 2006, p. 1).

Their impact was immediate. John Zeeben, who pitched for the 1952 Kamsack Cyclones, remembered how unrefined the local players were in comparison to their American teammates, noting that the prairie boys often lacked the polish and finesse the imported players brought to the field. (Jensen, n.d.). More than just athletes, these players became figures of fascination and cultural exchange in predominantly white towns across the province.

By the time the 1940s drew to a close, the groundwork laid by barnstorming tours and outlaw ball had already shifted the baseball landscape across the prairies. The presence of African American players, once controversial or outright prohibited, had suddenly become a competitive asset and, in many communities, a source of excitement and pride. Their influence helped raise the calibre of the game in Saskatchewan just as the province was entering a new era. With the war over and people hungry for summer recreation and shared joy, baseball surged in popularity. The timing was perfect. The arrival of more African-descent athletes on Saskatchewan diamonds coincided with the return of crowds, community tournaments, and cross-border rivalries. This confluence of talent and postwar optimism ushered in what many now call the province’s Golden Age of Baseball.

The Golden Age of Baseball in Saskatchewan

After the Second World War, baseball in Saskatchewan roared back to life. Local and provincial leagues were eager for higher-stakes competition, drawing enthusiastic crowds to diamonds across the prairies. “They’re playing more baseball in Saskatchewan now than ever before,” one 1950 sports columnist observed, “and the fans are gobbling it up faster than the games come along” (“Sports Commentary on Playing Baseball in Saskatchewan,” 1950, p. 14).

The emotional tone in the stands had shifted dramatically since the early 1940s. As one account noted:

“[T]he awful dread that people had carried with them everywhere—even to baseball games—while the war was raging, was now a thing of the past. Sitting in the stands on a warm summer evening in 1949, you could feel, with no sense of guilt, that nothing was quite so important as the ball game you were lucky enough to be watching.” (Hack, Shury, & Committee, 1997, p. 177)

This renewed enthusiasm and growing interest in high-calibre competition helped spark what historian Barry Swanton and North Battleford Beavers coach Emile Francis later called Saskatchewan’s “Golden Age of Baseball” (Swanton, 2006, p. 5; Hack, Shury, & Committee, 1997, p. 175). From the smallest rural communities to major centres, the province was alive with baseball, league games, tournaments, exhibition matches, and cross-border challenges.

Small-town teams recruited from the United States. With the independence of outlaw leagues and the allure of postwar optimism, baseball became more than a pastime; it became a community rallying point and a symbol of possibility. Into this thriving and evolving world of prairie baseball stepped the Indian Head Rockets.

Indian Head Rockets – 1950

In one of the most ambitious sporting ventures ever undertaken by a Saskatchewan town, the community of Indian Head announced on April 28, 1950, that it had secured a professional baseball team. They were backed by both the Indian Head Athletic Association and the Rockets committee, and the town committed to financing what was estimated to be a $6,000 to $7,000 monthly payroll for a roster of elite ballplayers, many of whom had been released by American teams. The deal was rumoured to have been brokered through baseball legend Rogers Hornsby, then manager of the Dallas Texans, who promised to deliver a 12-man team complete with a playing manager. While Indian Head initially asked for an all-white team, Hornsby and local organizer Jimmy Robison, who also served as Mayor and head of the Rockets committee, ultimately prioritized talent over race, assembling a formidable, African American roster primarily drawn from the Jacksonville Eagles and other Negro League affiliates. (1950 Indian Head Rockets, n.d.) Over the following weeks, as the Eagles played out their spring schedule across the American South, Indian Head finalized arrangements, including radio broadcasts on CKRM and a promotional push across the prairies. Representatives even traveled to Wichita, Kansas, home of the National Baseball Congress, to cement the deal. By June 1, a new team, soon to be known as the Indian Head Rockets, was en route to Saskatchewan, ready to play an estimated 60-game season and compete for more than $66,000 in prize money on the Western Canadian tournament trail.

The newly minted Indian Head Rockets hit a rough patch before they ever stepped onto Saskatchewan soil. After being rebranded from the Jacksonville Eagles and officially adopting the Rockets name for the Summer, with custom uniforms stitched with “Indian Head” and a painted 26-passenger team bus, the all-Black professional club was expected to make a splash on the Canadian tournament scene. But a series of transportation breakdowns derailed their first major opportunity.

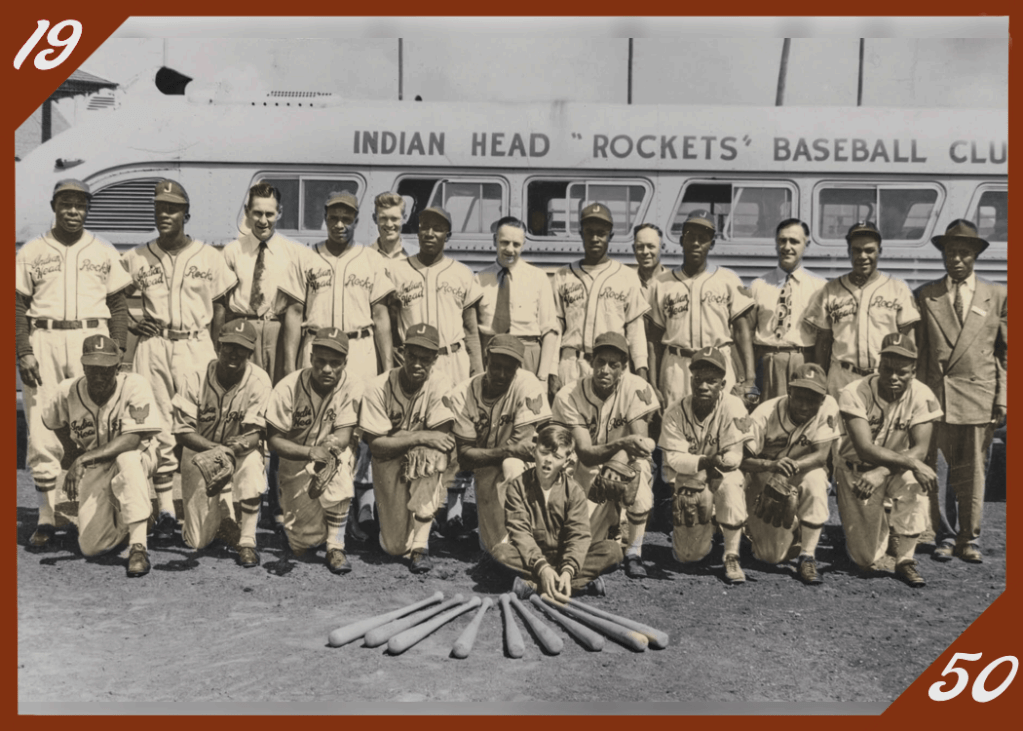

1950 Rockets Team -Photo Credit: Indian Head Museum, IHM.2021.0148

L to R: Big Jim Williams (Manager), unknown, Steve Nixon, Wesley “Doc” Dennis, Dick Jewitt, Dan Jenkins, Jimmy Robison, unknown, Les Booker, Horace Latham, Jack Watts, Jim Morrow, James ‘Cutprice’ Washington (Owner of the Jacksonville Eagles) Front L to R: unknown, Jimmy Randolph, Lou Green, Isiah “Ike” Quarterman, Jesse Blackmon, Poncho Grey, Shedrick “BB” Green, Lindsay Carswell, Bat Boy: Doug Appleton

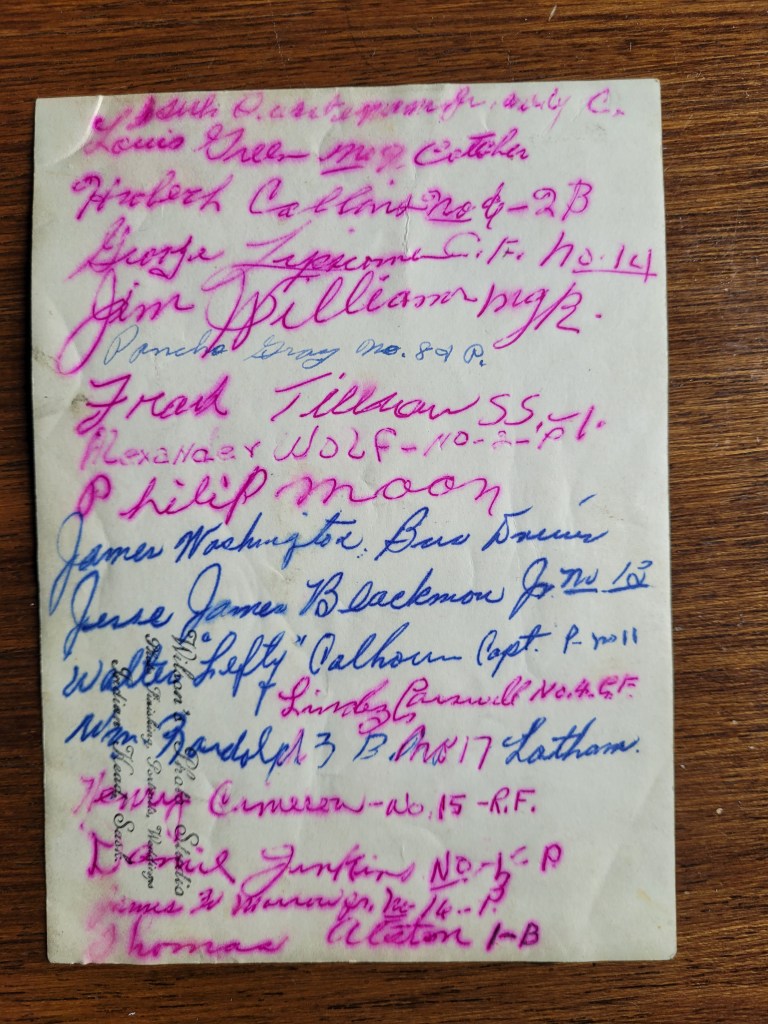

Autographs from the 1950 team. Photo credit: Indian Head Museum & the Gares Family

The team, managed by “Big” Jim Williams, was a 17-man powerhouse, seasoned and versatile despite being unaffiliated with any single league. Williams himself, a utility player-manager, was known for demanding high standards from his roster. He was tasked with whipping the team into shape after 15 days of travel-induced downtime.

The Rockets’ lineup was deep and well-balanced. Right-handed pitchers included Jesse Blackmon, Jim Morrow, Alexander Williams, and Cotshel Green, while Daniel Jenkins and Walter Calhoun handled duties from the left side. Louis Green and Henry ‘Red’ Cameron shared catching responsibilities. Around the infield, fans could expect George Washington at first base, Horace Latham at second, Holly Pane at third, and 17-year-old shortstop Spike Tillman, the youngest on the squad. William Randolph and Herbert Collins served as utility infielders. Outfielders included Lindsey Carswell, Isiah Quarterman, and Red Cameron, who also pulled double-duty behind the plate.

Despite further delays, including a doubleheader in Saskatoon being postponed when the team bus broke down again, this time in Minot, North Dakota, the Rockets finally made their home field debut on Sunday, June 11, 1950, with a spirited public workout at the Indian Head Exhibition Grounds.

According to the Indian Head News, the crowd gathered “almost in a twinkling,” growing into the hundreds as word spread. What they saw was nothing short of dazzling. Deep outfield throws, lightning-fast double plays, and sharply executed base work impressed even the most seasoned “railbirds” in the stands. The Rockets, rusty after two weeks of road delays, were driven hard by Williams, but responded with grit and flair. For Indian Head, this was more than baseball. It was the arrival of something special.

1952 – Nat Bates and Willie Reed join the team

Despite the early hurdles, the Indian Head Rockets quickly found their rhythm, dazzling prairie crowds with a level of athleticism and professionalism rarely seen on local diamonds. By 1952, the team had hit its stride, welcoming new talent, including two players who would leave a legacy in Saskatchewan baseball: Nat Bates and Willie Reed. Their arrival marked a high point in the Rockets’ story, both for their skill on the field and for the way they connected with the communities they visited.

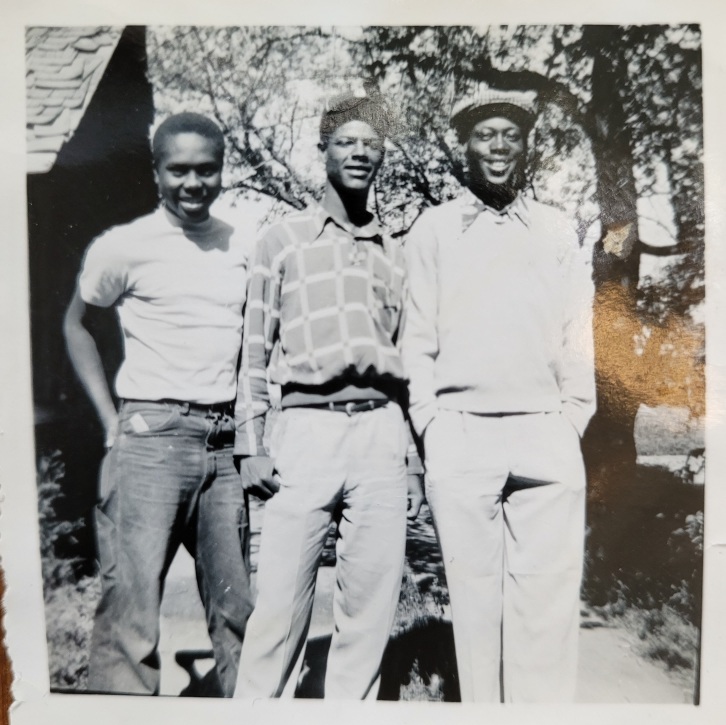

Nat and Willie first came north from California in 1951 to join the Medicine Hat Mohawks, part of a wave of young African descent college players who barnstormed across the prairies with speed, energy, and heart.

Read more about their time with Medicine Hat Mohawks: https://albertadugoutstories.com/2023/12/19/three-prairie-baseball-icons-reunite-after-72-years/

When Nat and Willie joined the Rockets in 1952, they didn’t just play; they made an impact. Nat, a calm and gutsy pitcher, and Willie, a quick and consistent second baseman, anchored a team that thrilled fans across the province. They were welcomed into homes and communities, building bridges across cultures at a time when segregation still ruled much of the United States.

Their influence extended far beyond the diamond. Nat went on to serve in the military and became a long-serving city councillor and two-term mayor in Richmond, California. Willie built a life grounded in faith, family, and quiet leadership. They never in a million years would think they would return to Canada so many years later.

A Tribute on the Field: 75 Years After the Rockets’ Debut

Wearing my Vice-President of the Indian Head Museum hat, my idea for the tribute game began with a simple thought: what better way to honour the Indian Head Rockets than by bringing their story back to the ball diamond, where it started, and into the hearts of a new generation of fans? I wanted to continue telling their story in a way that felt alive, immediate, and rooted in place. Baseball has always been about more than the game; it’s about memory, connection, and community. And for the Rockets, their story deserved to be told not just in museums or archives, but on the field, under the prairie sky.

The connection between Indian Head and Regina made the location even more fitting. For many years, teams from the Queen City competed in Indian Head tournaments. In 1953, Rockets player-manager Big Jim Williams brought the team to Regina to play for the Regina Capitals (Caps). That shared history formed a bridge across time, making Currie Field the perfect setting for the tribute game.

As Red Sox President Gary Brotzel said, speaking in a Sports Cage interview, “As soon as they brought the idea, I said, ‘Yeah, we got to do this.’” He remembered a story the late Gord Currie once told him about coaching the Junior Red Sox against the Rockets back in the early 1950s. “They played this great, unbelievably talented team of Black athletes mostly from the States. He said they got no-hit but did manage to steal second, and thought maybe they’d even faced Satchel Paige once.” (The SportsCage, 2025)

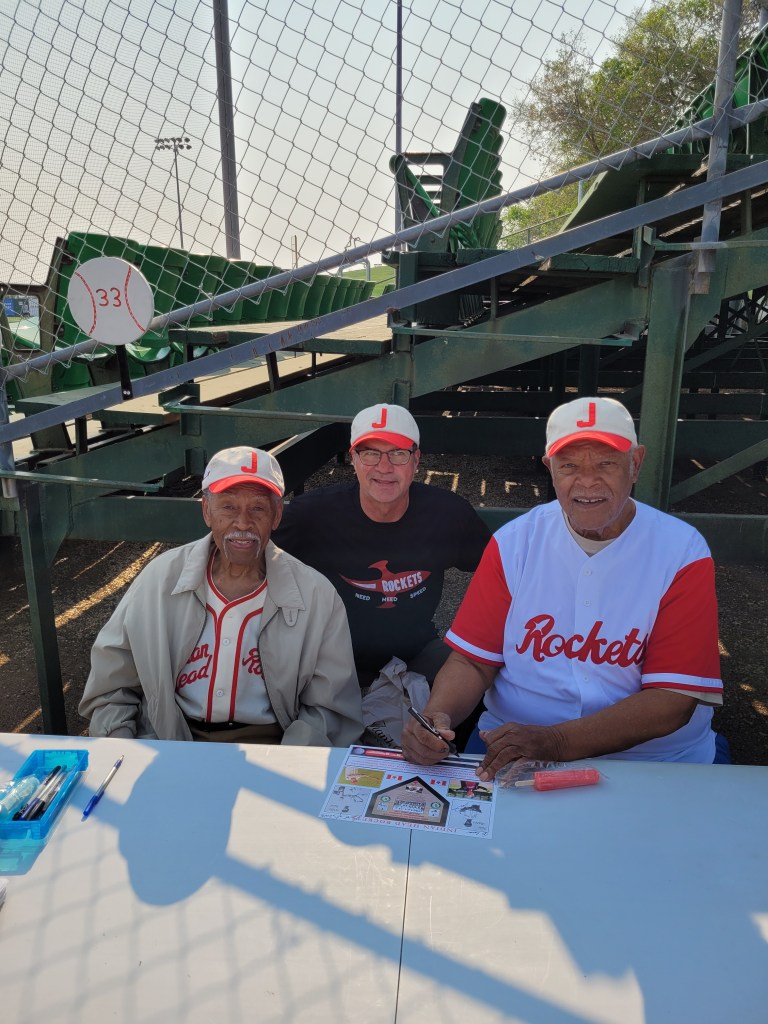

Gary’s support meant a lot, and I appreciated how much curiosity and care he and executive director Sharon Clarke brought to the process. “Robyn Jensen’s just been fantastic to work with and is just loaded with knowledge,” he shared. “I’ve learned more in the last month than I ever knew about baseball in the ’50s and all the barnstorming and everything that was going on. It’s a neat story.”

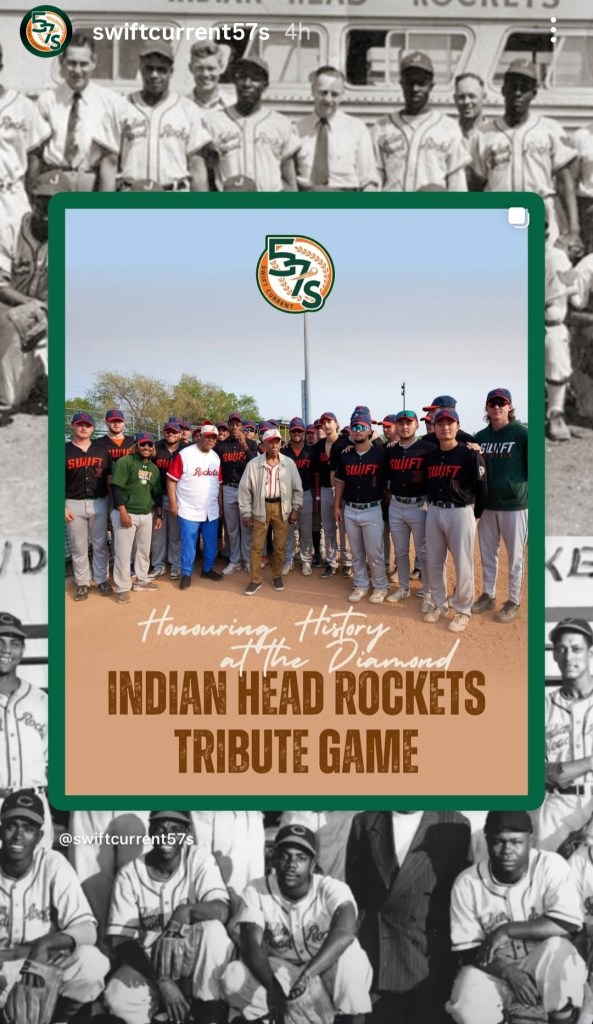

On June 11, 2025, seventy-five years to the day since the Rockets made their home debut with a spirited public workout at the Indian Head Exhibition Grounds, the past came to life again. The Regina Red Sox and the Swift Current 57s wore commemorative hats, honouring the style and spirit of the original team. The stands were filled with families, long-time fans, and newcomers alike, many of whom were learning the Rockets’ story for the very first time.

Before the first pitch, I stepped up to the microphone to offer a welcome and a reminder of why we were all there. I spoke from the heart, sharing thanks to those who helped bring the tribute to life: from the Regina Red Sox and Swift Current 57s to the Saskatchewan African Canadian Heritage Museum, Halter Media, and the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame. I thanked the Lieutenant Governor, the mayors of Indian Head and Regina, and the many community members who had made the journey to be there, including the Indian Head U18 team, who joined us for the opening ceremonies. I also acknowledged the two researchers who’ve meant so much to this journey: Jay-Dell Mah and Rich Necker. I, along with Jay-Dell’s speech, gave a version in 2022 at the opening of the Indian Head Rockets exhibit. Honouring his voice and the community behind this story felt just as important as telling the history itself.

I reminded the crowd that two former Major Leaguers Tom Alston and Pumpsie Green, once played for the Rockets, and that Roberto “Chico” Barbon, who joined the team in 1953, went on to become the first Latin American to play in Japan’s major leagues. The Rockets were no ordinary team. They emerged from the shifting tides after Jackie Robinson broke the colour barrier in 1947, when opportunities in the Negro Leagues were fading and new chances were being found in Canadian towns like Indian Head. They didn’t just play, they connected across borders, races, and generations. (Watch the full speech here: https://youtu.be/shvz6tKVgIs)

But no tribute could match the presence of living history.

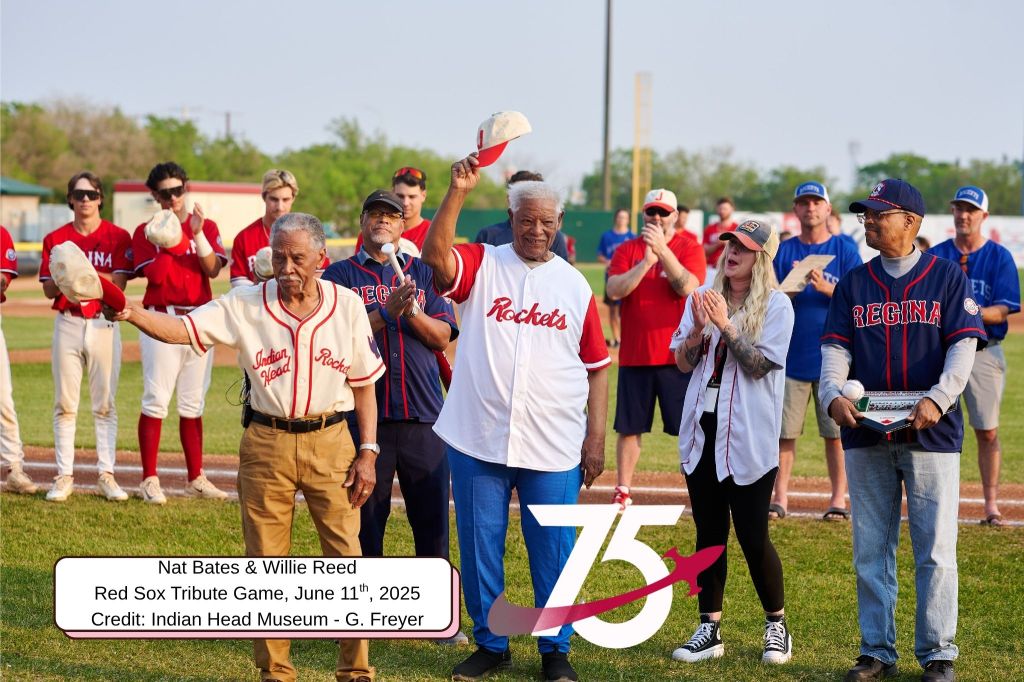

When Nat Bates and Willie Reed, two former Rockets and the last known surviving members of the team, stepped onto the field, the crowd rose in a thunderous standing ovation. Both men tipped their hats to the stands. It was a powerful moment, one that said everything. A gesture of respect to their teammates long gone, to the communities that welcomed them more than 70 years ago, and to the young fans now cheering from the same sidelines they once played beside.

As Gary reflected on that moment, he remembered something Nat had said to him during our planning call: “I can’t believe you guys would want us back after 75 years.” That humility floored him. “They were treated in Indian Head just like everybody else in town,” Gary added. “He could go to the restaurants, ride the bus, come to Regina—and everyone treated him very well.”

The ceremonial first pitch followed, but by then, the night had already achieved what it set out to do. It had turned memory into motion, history into presence, and celebrated the legacy of a team that gave Saskatchewan more than wins. It gave the province a glimpse of the future through the courage and excellence of men like Nat and Willie, who helped change the game and the hearts of those who watched it.

Final Reflections: A Night to Remember

As the final out was called and the scoreboard lit up with a 9–4 win for the Swift Current 57s, it was clear that the night had been about far more than the score. For everyone on the field, it was a game they wouldn’t soon forget.

“It was an amazing experience the Regina Red Sox put together,” said Ruddy Estrella, head coach of the Swift Current 57s. They wore hats representing the Florida Cubans, who played as the Indian Head Rockets in 1953 and 1954. “For the Swift Current 57s—Floridian Cubans for the night—it was an honour to be part of it and to get a win on such a special night. It was great to meet Robyn, who worked so hard to make this happen, from the card giveaways to having two great legends, Willie Reed and Nat Bates, speak to our young players. Their wisdom and words meant a lot to me as a coach, and even more to the kids, who really listened and took those words to heart.”

Swift Current assistant coach Kenny Jinks echoed that sentiment: “It was a privilege to play in the Indian Head Rockets game as the away team. The game was a real battle, with both sides giving it their all. In the end, we came out on top, but it was a tight and competitive game. Big thanks to everyone who made the event possible—it was an honor to be part of it.”

For Regina Red Sox manager coach Rye Pothakos, the night was a powerful reminder of baseball’s enduring role in connecting people across generations: “The Indian Head evening at Currie Field was a celebration of baseball and a night that bridged generations. Meeting Nat and Willie was an honour and a baseball memory I will always cherish. Thank you to Robyn and all the organizers for a truly wonderful event.”

The game may be over, but the legacy lives on, through the players who took the field, the fans who showed up to listen and learn, and the history that was brought home, once again, under the lights of a prairie diamond.

Reflections from Nat Bates and Willie Reed

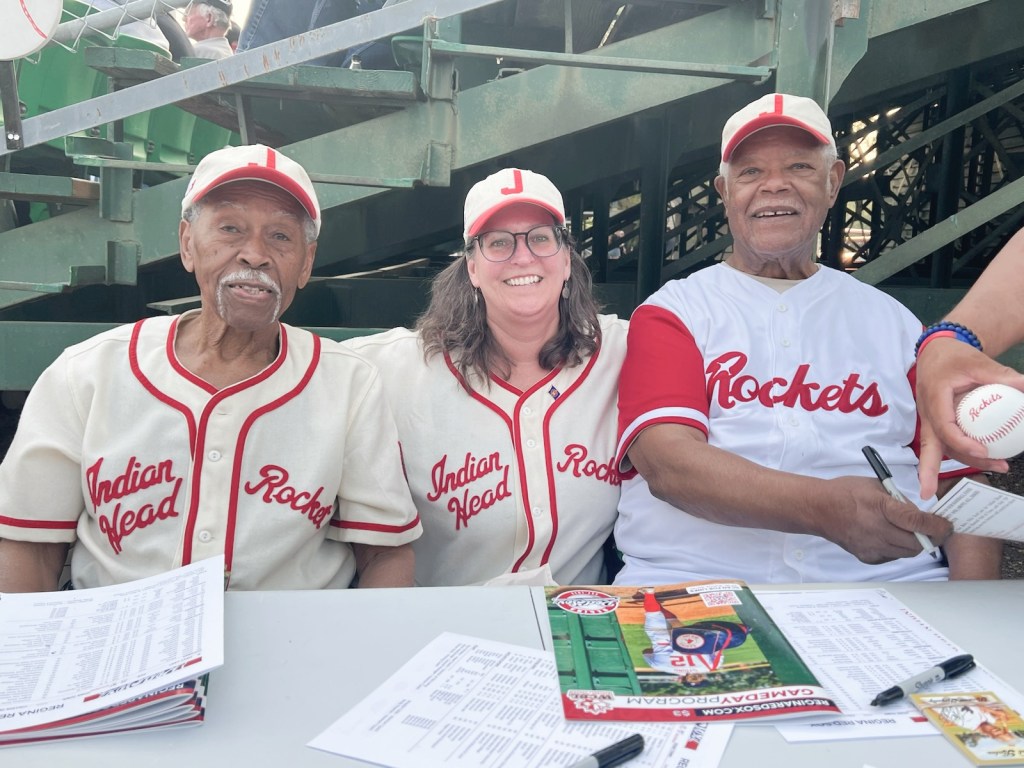

It’s been seventy-three years since they first played in Saskatchewan, yet Nat Bates and Willie Reed’s memories remain vivid, and their gratitude, profound. (The SportsCage, 2025a)

Nat Bates, starting pitcher for the Rockets and a Saskatchewan Baseball Hall of Fame inductee, has visited Saskatchewan three times in the past few years. “Each time I come here, it’s just beautiful,” he said. “The reception is so outstanding. I couldn’t ask for anything better.”

For Willie Reed, also a Saskatchewan Baseball Hall of Fame inductee and second baseman, this was his first trip back since 1952. “I was supposed to come with Nat the same time before, but had surgery, so I couldn’t make it,” he shared. “I’m so happy to be here now, though.”

When asked about their initial reaction to the call inviting them to play baseball in Indian Head back in the early 1950s, Willie recalled, “I had been here with the California Mohawks in 1951. We decided to come back in 1952 with the Indian Head Rockets. It was a pleasure to be on an all-Black baseball team—some from the South, some from California, and we really enjoyed it.”

Nat remembers that call as exciting. “We had a successful season with Medicine Hat Mohawks,” he explained, “then five of us from that team, including Willie Reed, Pumpsie Green (who later went to the Boston Red Sox), Emmett Neil (who was sadly killed in Korea), Winters Calvin, and myself—joined the Indian Head Rockets. We just wanted to play baseball and pursue our careers. We didn’t even know it was going to be an all-Black team until we got there.”

Reflecting on playing in Saskatchewan, Willie spoke warmly of the community and fans: “Canadian people really love baseball and treated us like we’d been here before. It wasn’t a surprise to them but it was to us.”

Nat, as a pitcher, recalled the stark contrast in racial experiences between California and the American South. “In Canada, your ancestors showered us with nothing but appreciation, respect, and love—something we hadn’t experienced to that degree even in California. Pitching in front of a fan base like that was fantastic. Fans supported us 100%. When we traveled to Swift Current, Lethbridge, and Edmonton, the fans followed us and it was like family.”

Willie shared a memorable moment from a Calgary tournament where Pumpsie Green had an incredible game with eight hits in a doubleheader, a feat Willie said he’d never seen before.

Nat also recalled the intense tournament circuit, winning many with prize money up to $25,000, though the management never shared the money with the players. “It wasn’t about the money. It was about achievement, success, and teamwork,” he said. “We didn’t fight among ourselves; the fans rooted for all of us. Canadian fans appreciated good baseball and applauded visiting teams just like they were their own.”

Willie described the pride of wearing the Rockets’ jersey again: “It’s amazing…I never thought this would happen. I’m proud and honoured by all of you.”

Nat offered heartfelt advice to young athletes today:

“Play the game as hard as you can. Learn from it. Respect your coaches and teammates from all backgrounds. Learn discipline and control. Winning is great, but be strong enough to handle loss with humility. Not everyone will make it to the major leagues, but the lessons you learn in baseball and sports will help you work with others and succeed later in life, whether as a teacher, police officer, or anything else.”

Both Nat and Willie, soon to be 94 years old, expressed deep gratitude:

“This has been a magnificent job of representing the community and respecting what we tried to accomplish 75 years ago. We can’t thank you enough.”

As they returned to the diamond one last time, the cheers from Currie Field echoed a timeless welcome: once a Rocket, always a Rocket.

Willie, Robyn and Nat. Photo Credit: Amber Anderson

Personal Reflection – Why This History, Why This Project

I didn’t set out to organize a tribute game, launch a baseball card series, or curate exhibits about the Indian Head Rockets. It started with curiousity, about the town I moved to 20 years ago, about a photograph my daughter found, and about why no one had told me that Saskatchewan once had a professional African-descent baseball team. The more I learned, the more I realized that this wasn’t just a story about sports. It was a story about movement, memory, resilience, and the way communities change, sometimes quietly, sometimes in extraordinary ways.

As a historian, genealogist, and curator, I’ve always been drawn to the margins of archives, those places where stories live but aren’t always named. When I came across the Indian Head Rockets, I felt an immediate pull. These weren’t just players passing through; they were men who left a mark. They played with grace and grit at a time when the colour of their skin closed more doors than it opened. And yet, here on the Canadian prairie, they, as baseball players, found something rare: welcome.

That sense of welcome, of unlikely belonging, resonated deeply. It made me wonder what it meant for them, for the communities they visited, and for those of us now trying to understand who we are and where we come from.

This project, whether in the form of an exhibit, a card set, a tribute game, or a classroom visit, is my way of answering that call. I wanted to tell the story in as many ways as it deserved to be told. To let it live not just in display cases or books, but in ballparks, conversations, classrooms, and shared memories. To bring the history home.

For me, history isn’t just about what happened. It’s about who remembers, and why. This project has been a way of remembering out loud and inviting others to remember with me.

Looking Ahead: Carrying the Story Forward

The tribute game may be over, but the work of remembrance continues. The legacy of the Indian Head Rockets is no longer tucked away in fading newspaper clippings or forgotten photographs; it’s alive in the voices of Nat Bates and Willie Reed, in the cheers from the stands, and in every child who picks up a commemorative card also created for the 75th and asks, “Who were they?” I hope that this story continues to ripple outward, into schoolrooms, museum galleries, family conversations, and future community projects. There is still so much more to uncover, honour, and celebrate. The Rockets remind us that history is not just behind us, it’s something we carry forward, together, pitch by pitch, generation by generation.

References:

1950 Indian Head Rockets. (n.d.). https://www.attheplate.com/wcbl/teams_rockets3.html

Hack, P., Shury, D. W., & Committee, S. S. H. O. F. a. M. S. H. P. (1997). Wheat Province Diamonds : a Story of Saskatchewan Baseball. Regina, Sask. : Sport History Project Committee, Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame and Museum.

Jensen, R. (n.d.). Interview with John Zeeben, 2023 [Dataset].

Mah, J.-D., & Necker, R. (2023). Outlaw Baseball & Dick Brookins [E-mail].

Necker, R. (n.d.-b). Dick Brookins. Retrieved from https://attheplate.com/wcbl/profile_brookins_dick.html

[Sports Commentary on playing baseball in Saskatchewan]. (1950, August 4). Lethbridge-Herald, p. 14.

Swanton, B. (2006). The ManDak League: Haven for Former Negro League Ballplayers, 1950-1957. McFarland & Company Inc.

The SportsCage. (2025, June 12). The SportsCage: Honouring the 1952 Indian Head Rockets with Regina Red Sox’ Gary Brotzel [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z4_StiEYwrI

The SportsCage. (2025a, June 12). The SportsCage: 1952 Indian head rockets Nat Bates and Willie Reed [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mCQWy2zAq20