Prologue

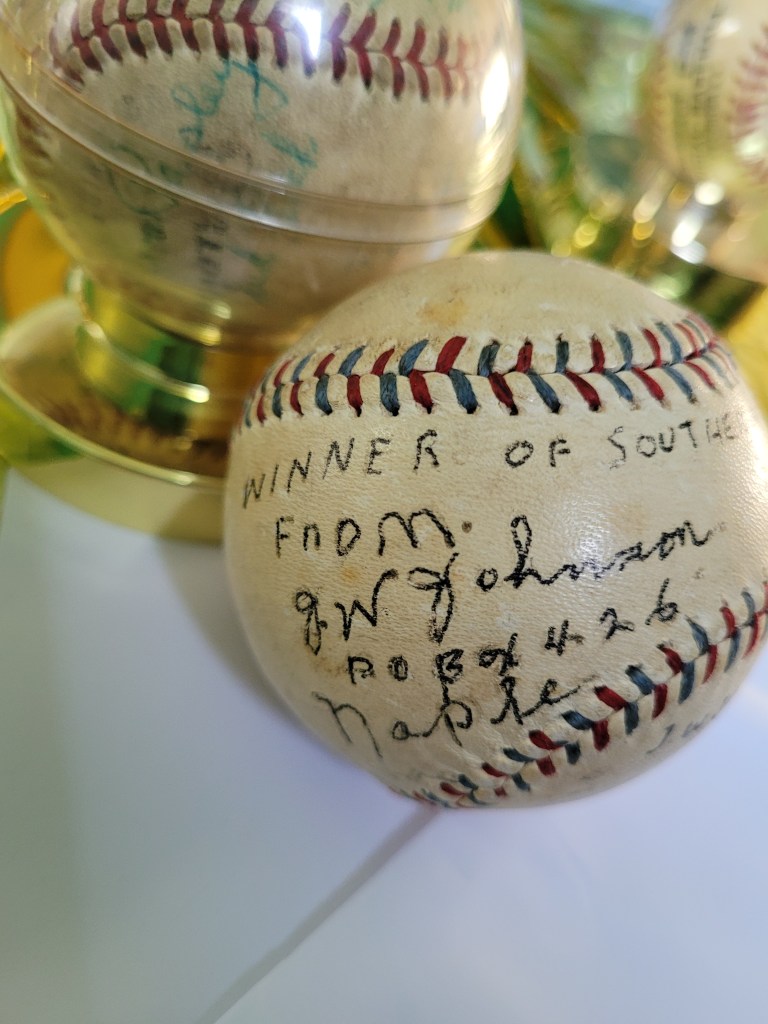

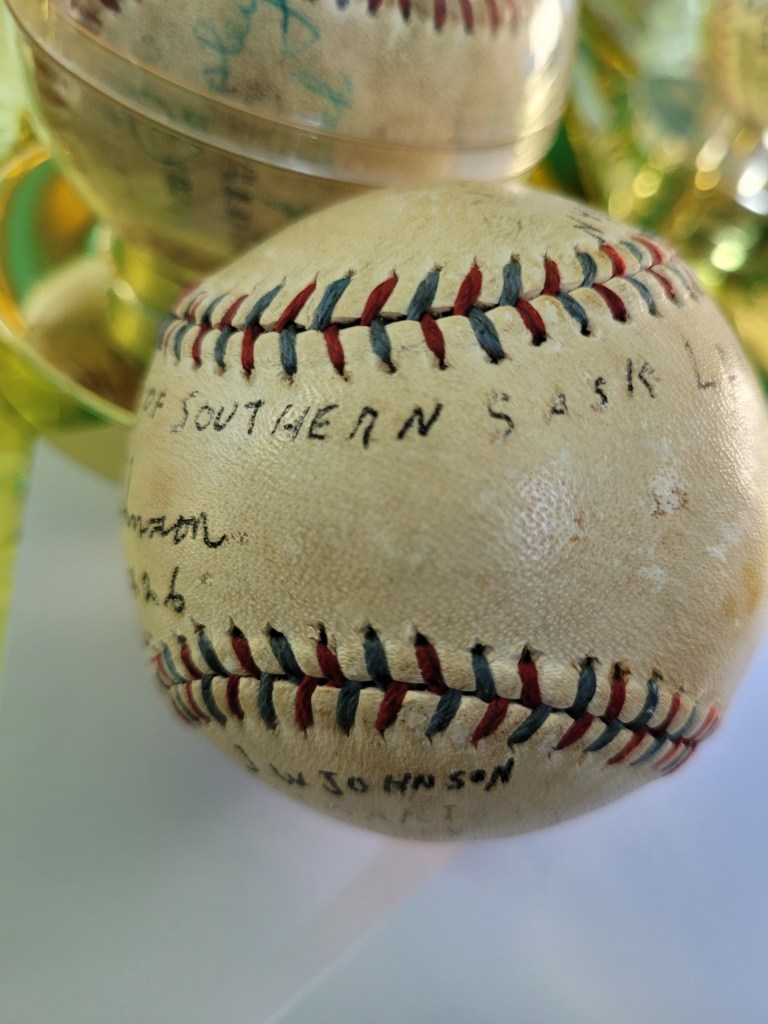

It began, as many research rabbit holes do, with an object. I thought it would be straightforward, but the moment I began cross-referencing the names on the ball with the 1940 Southern Saskatchewan League (SBBL) champions — the Weyburn Beavers — something didn’t add up. The names didn’t match. What was this ball? Here’s the story:

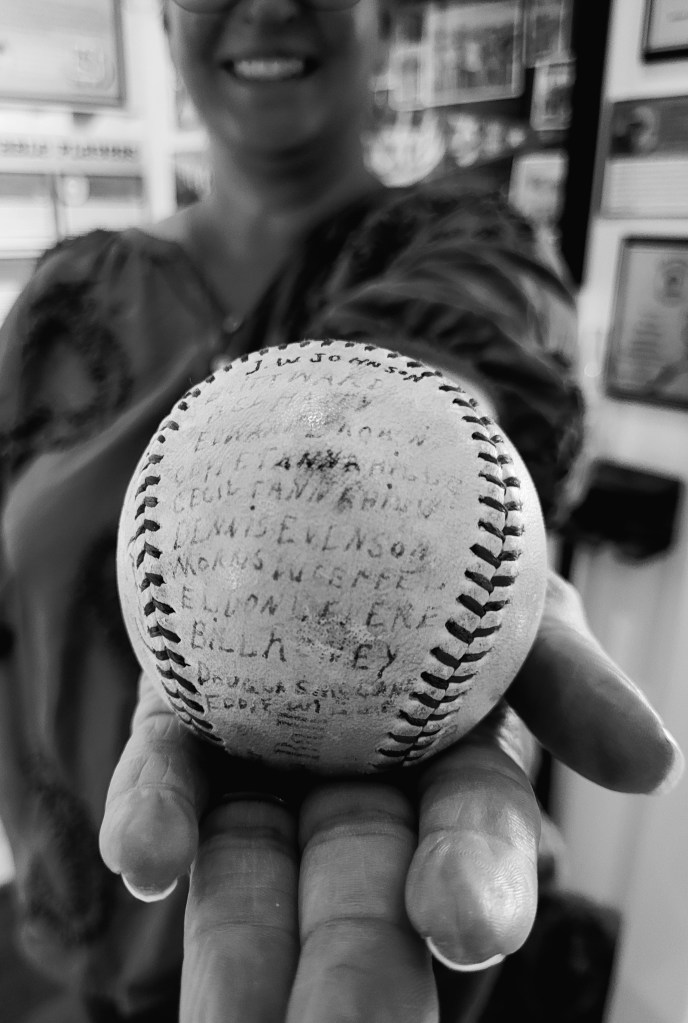

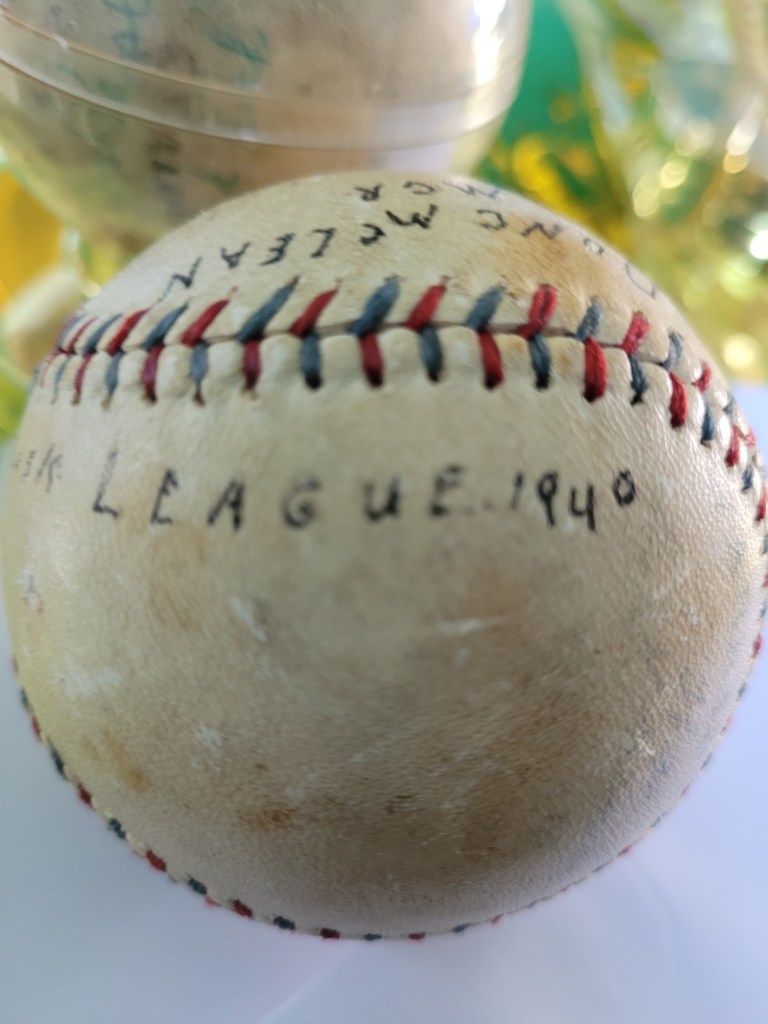

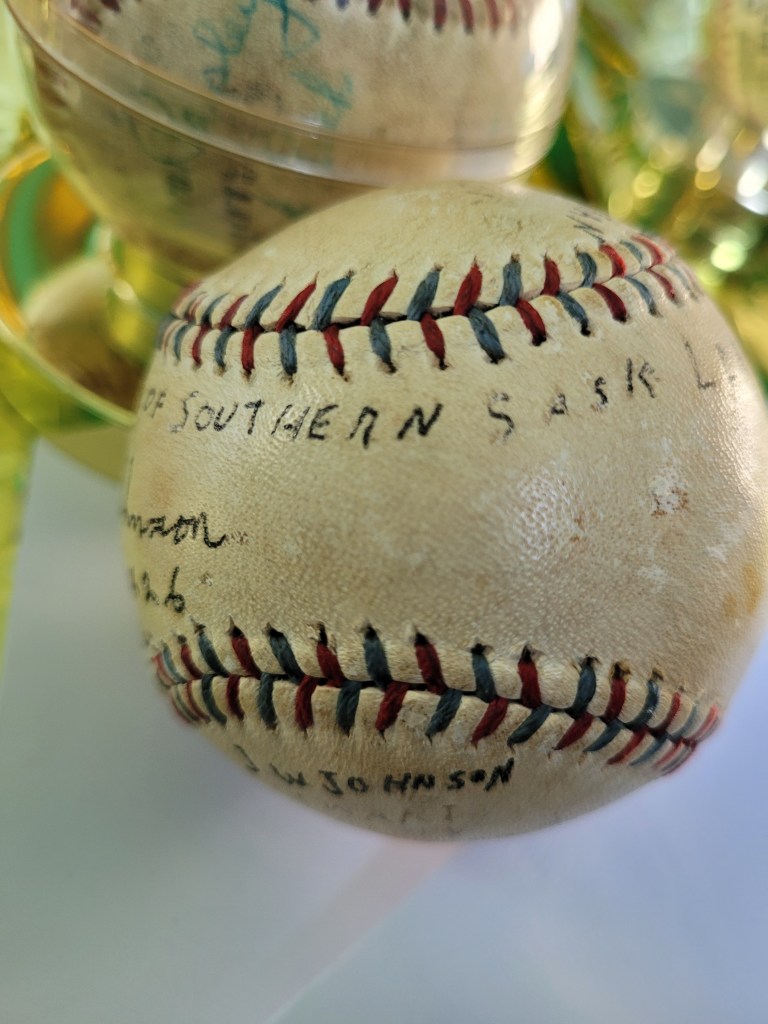

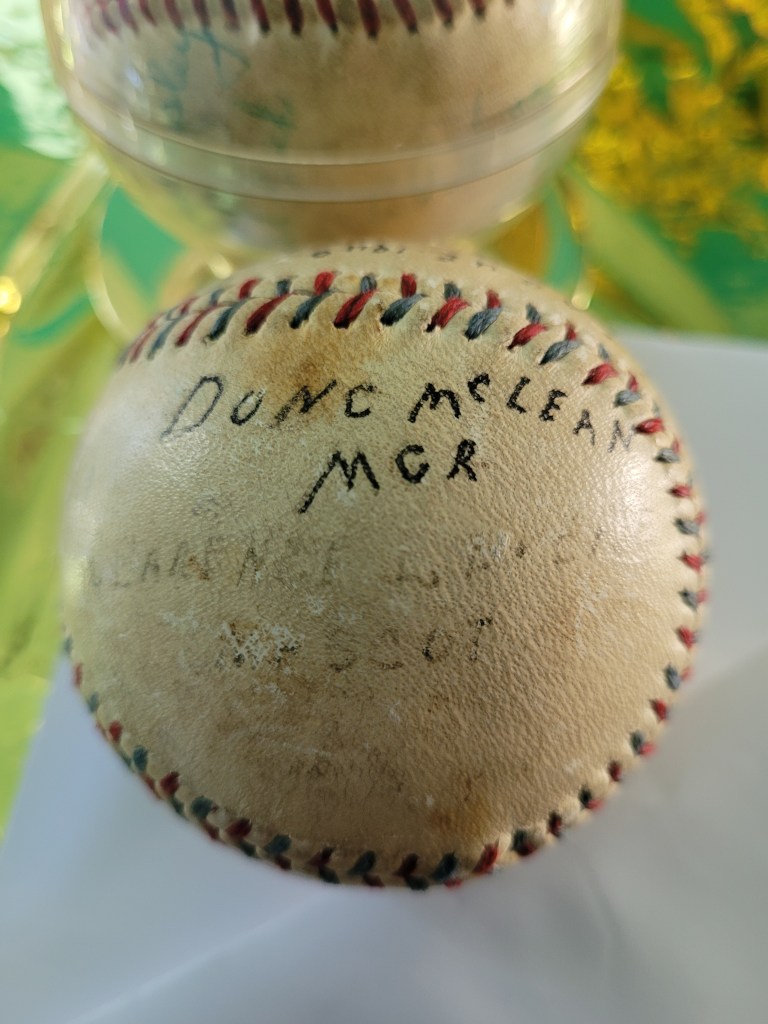

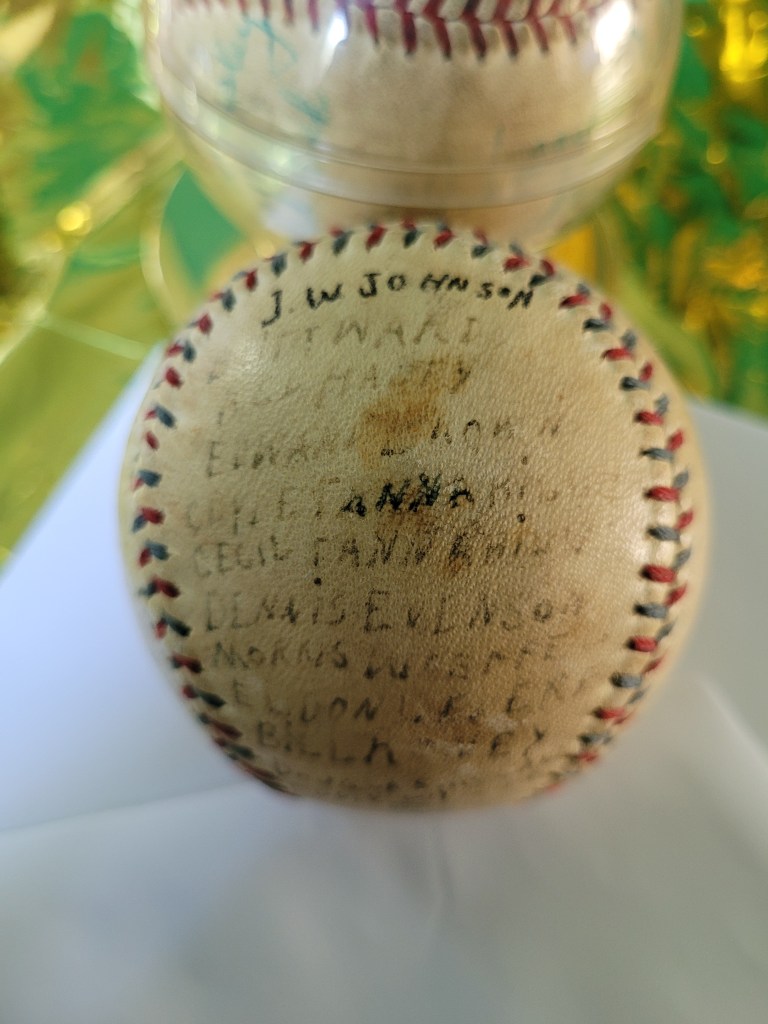

I saw a lot online through our local auction house, and in it, a group of four baseballs. One caught my eye. Just under the double stitches of a yellowed, scuffed “Cork Center Official League Ball” was written Winner of the Southern Sask League 1940. The leather bore printed names in fading ink, some traced over by a surer hand. I could make out “J.W. Johnson” and “From G.W. Johnson PO Box 426, Naple,” (Naple is a town located in Texas) along with “Dunc McLean, MGR.” I didn’t yet know the whole story, but I knew the ball had belonged to someone, and in their hands, it must have been something very special. I bid on it, of course, and won!

The moment reminded me of part of my master’s thesis research on orphaned photographs. When an object is removed from its original owner, it loses one narrative but can gain another. It can be “reactivated,” its meaning renewed when placed in a new context, or when fragments of its story are pieced together. This baseball was no longer just cork, hide, and stitching; with its original owner gone, I wanted to find this ball’s story and see what it was waiting to tell me.

I turned to attheplate.com, my go-to starting point for all my prairie baseball research. Sure enough, it confirmed that the Weyburn Beavers had won the SSBL in 1940. Cool. But when I compared the names on the ball to the Beavers’ roster, none of them matched. I should have known by now that research is rarely a straight line. There are always curveballs (pun intended), and this was one of them.

The signatures eventually led me to the 1940 Liberty Eagles, a team that was the dominant force in SSBL and leaders going into the semi-finals.

Let’s start at the Beginning

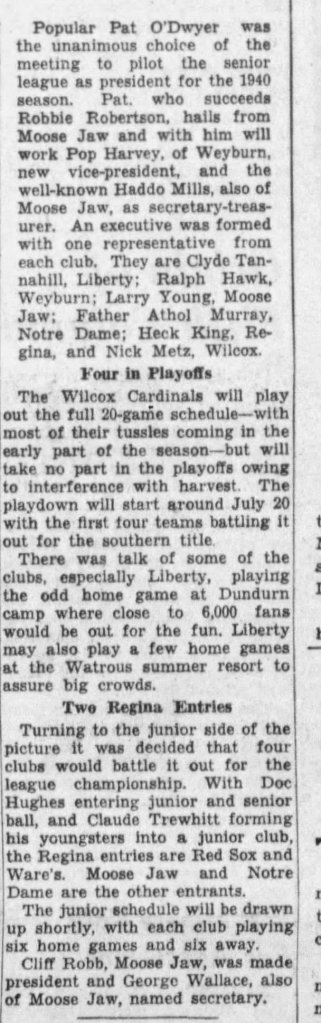

In May, the newspapers provided detailed information about the upcoming SSBL Season, a unanimous vote placed sportswriter Pat O’Dywer as its president, and representatives from each club. Six teams were playing, but only five were committed to the play-offs. The Wilcox Cardinals would only play their 20-game schedule until harvest. The remaining teams, Notre Dame, Weyburn Beavers, Moose Jaw Elks, Regina Red Sox, and Liberty Eagles, would play for a spot in the semi-finals. According to O’Dwyer in his August 09th article, the league committee also agreed to have a flexible schedule “subject to readjustment based on agreement between managers of clubs concerned.” (O’Dywer) At least three teams were noted as having imported players from the United States: Moose Jaw, Liberty, and Regina. Some were adding them later in the season.

On paper, things appeared organized. Teams were stocked, the schedule was adaptable, and there was genuine anticipation for the summer ahead. The way it was framed in print, one might think the 1940 season would unfold with good sportsmanship and smooth sailing. But as the weeks wore on, disputes over imports, protests, and withdrawals turned what looked like a model season into something much further from the truth.

First Problem: Notre Dame

The first sign of trouble came mid-season with the withdrawal of Notre Dame. Their exit, while understandable given the wartime enlistments, disrupted the balance of the schedule and left the remaining clubs scrambling to fill dates. Liberty was upset that Notre Dame did not give them $25 for forfeiting their game to cover their expenses.

The loss of Notre Dame was the league’s first real disruption, but it didn’t slow the pace of play for the remaining contenders. Games continued through the summer heat, with rosters shifting and imported players joining late in the season to strengthen playoff bids. Despite the uneven schedule, the standings began to take shape, and by the close of the regular season, the Liberty Eagles had proven themselves the team to beat.

Regular Season Finishes – Final Standings

By the time the regular season ended, Liberty had finished at the top of the standings, setting up semi-final matchups: Liberty vs. Moose Jaw, and Weyburn vs. Regina. (https://attheplate.com/wcbl/1940_50i.html)

The Eagles finished the regular season at the top of the standings:

W L Pct.

Liberty Eagles – 13 7 .650

Weyburn Beavers – 12 8 .600

Moose Jaw Elks – 8 11 .421

Regina Red Sox – 9 15 .391

(*Records of withdrawn Wilcox Cardinals and Notre Dame not included)

Second Problem: The Boil-Over Game

By August 3, the Elks were fighting to keep their playoff hopes alive, and Liberty was looking to put the series out of reach. But the game at Ross Wells Park quickly turned into something far more combustible. In the first two innings, Elks Donnie McDonald’s grand slam and a string of extra-base hits gave Moose Jaw a 7–0 cushion. Liberty starter Hugh Crooks was battered for two home runs, four triples, and a double before the Eagles could regroup.

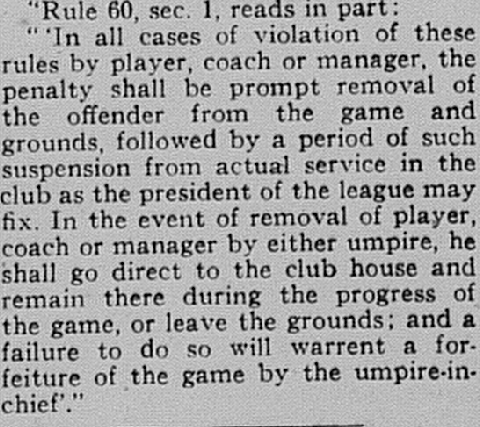

Then came the confrontation. When “Butch” McDonald struck out, his unwillingness to depart from the field quickly, followed by a “lengthy tirade” at plate umpire George Joyner, created an explosion. In an extraordinary move, Joyner awarded the game to Liberty on the spot due to Rule 60, sec. 1:

This ruling would have given the trailing Eagles an improbable, if hollow, victory. But after more heated discussions, Joyner reversed himself, and the game resumed. The Elks, behind Tony Maze’s steady pitching and Norm Larson’s heavy bat, went on to seal a 12–2 rout.

This was the turning of the tide for Liberty. Joyner’s reversal wasn’t merely a change of mind; to Eagles supporters, it was a public undermining that shifted the ground under their feet. In hindsight, August 3 was the hinge. What happened that night set in motion the protests, late-night telephone wrangling, and conflict of interest. Within days, the Liberty Eagles would be gone from the SSBL entirely.

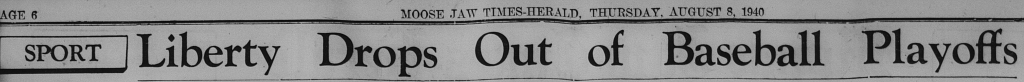

By August 8th, the headlines told the story: the Liberty Eagles were out. Both the Regina Leader-Post and the Moose Jaw Times-Herald reported that the team’s withdrawal was tied to the sudden departure of their four African American imports, a loss that crippled their roster and revived simmering debates about the role of imported players. It wasn’t the first time this had happened; the previous season, Liberty’s imports had also left at the end of July. But in 1940, with the stakes high and tempers already frayed because of the Moose Jaw game, it became the spark that lit the powder keg.

Problem Three: Outlaws, Imports, and Exclusion

In 1940, Saskatchewan sportswriters often referred to the SSBL as an “outlaw” circuit, a label that separated it from “Organized Baseball.” Organized Baseball meant the formal structure of the sport, from the major leagues down through affiliated minor leagues and provincial amateur associations. It also carried the shadow of the U.S. game’s unwritten racial segregation, which barred African-descent players from the majors and their minor-league affiliates.

By contrast, outlaw leagues like the SSBL operated entirely outside those constraints. They could sign whoever they pleased, from Negro Leagues stars to barnstorming pros, with no residency rules or eligibility restrictions to answer to. Since the collapse of the Western Canada Baseball League in 1921, most senior leagues in Saskatchewan were technically “outlaw,” and many, such as the Broadview Buffaloes of the 1930s, thrived precisely because they could bring in talent from anywhere.

Problem Four: O’Dwyer

But that freedom came under fire in the summer of 1940. As Leader-Post columnist Pat O’Dywer, who was also president of the SSBL, recounted in his August 9 piece “Liberty Tosses in the Towel,” some clubs began pushing for limits on “imports.” At the time, there were no boundaries, or formal restrictions, on O’Dwyer as league president, to present opinions as a news reporter.

O’Dwyer should have been expected to act impartially and uphold the principles of fair play. However, in his role as a journalist, he actively shaped the narrative surrounding Liberty’s withdrawal and the resulting league turmoil, often using humor to mock dissent. For example, he likens critics to “the purrr of kittens parked around a milk pail” and dismisses Liberty manager Duncan McLean’s protests as mere sour grapes, writing that “‘We wuz robbed,’ was the general tone of the complaint.”

While the season began without restrictions, tensions flared as playoffs approached. The SSBL executive imposed a new rule: no more than four imports could appear in a playoff lineup.

The spark came when Doc Hughes, owner of the Regina Red Sox and, notably, an African American baseball entrepreneur working in Saskatchewan, protested the Moose Jaw Elks’ late-season importation of African-decent star players. His complaint prompted meetings, press coverage, and ultimately the four-import limit. The fallout was immediate: multiple teams threatened to quit, and Liberty, upset by shifting rules and playoff disputes, withdrew from the semifinals just one win from advancing.

The irony ran deep. Hughes’s protest targeted Moose Jaw, but the rule he helped set in motion also applied to Liberty, whose roster included four African-American imports of their own. In effect, the new limit curtailed the number of players who could appear in the decisive games, not just for opponents, but for Hughes’s club and Liberty alike.

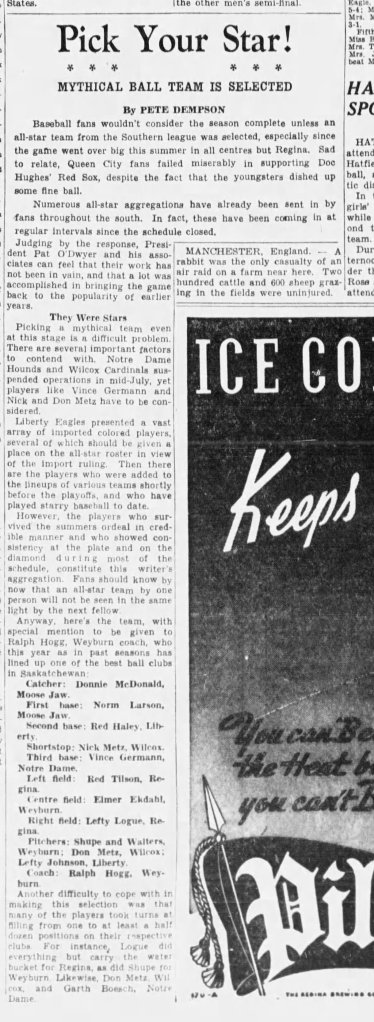

Yet even with these new restrictions, African-American players still left an undeniable mark on the 1940 season. Red Haley, Liberty’s star infielder, was named to the league’s mythical all-star team, a roster compiled from the top performers of the year, and finished third in batting average. His selection was a testament not only to his skill but to the central role African-American imports played in raising the competitive level of the league.

Frustrations Galore

While Haley’s achievements reflected the high calibre of play, the season’s closing weeks were marred by escalating disputes between Liberty and the league’s leadership. A series of scheduling changes, questionable rulings, and perceived favoritism toward rival clubs strained relations to the breaking point. What followed was a public back-and-forth in the press, Liberty’s version of events versus that of league president and sportswriter Pat O’Dwyer, which revealed deep divisions in how the SSBL was being run.

Liberty Responds

Liberty Eagles Dennis Evenson writes a rebuttal in the August 13 edition of the Leader Post in response to Pat O’Dywer’s article:

One problem came earlier in the season when Notre Dame, scheduled for a doubleheader against Liberty, pulled out citing “lack of players.” Liberty officials were incensed when many of those same players were later seen competing in summer tournaments. The cancellations cost Liberty both their travel expense reimbursement and the gate receipts from two games. When Liberty sought the $25 forfeit fee, the league quietly awarded it to Notre Dame without consulting the other teams.

The playoffs brought further conflict. Because of the Regina Exhibition, the Moose Jaw–Liberty semifinal was played a week earlier than the Regina–Weyburn series, pushing the finals into harvest season when many players were needed on farms. As regular-season champions, Liberty expected to open the series at home, per league tradition, but were ordered to start in Moose Jaw to align with a civic half-day holiday. Moose Jaw fielded an all-import lineup, but Liberty won the opener 6–2.

In Game Two, Evenson concurs with O’Dwyer. With Moose Jaw leading 12–1, their player Butch McDonald was ordered off the field but refused to leave. Umpire Joyner abruptly awarded the game to Liberty, only to reverse his decision after Liberty manager Duncan McLean urged him to resume play in the name of sportsmanship. Moose Jaw went on to win 12–2.

After a rainout in Game Three, Liberty won the makeup 2–1. Game Four was initially set for Wednesday, but Moose Jaw rescheduled it to Thursday, a day after Liberty’s imports had to leave for home. The Eagles still fielded a team, but the league then announced in the papers that any deciding Game Five would be played in Moose Jaw, despite Liberty’s first-place standing giving them the right to host.

For Liberty manager Dunc McLean, if Game Two was the boiling point, Game Five was the breaking point. He told O’Dwyer that if the league insisted on Moose Jaw hosting, Liberty would retroactively claim the forfeited Game Two and take the series 3–0. When the dispute went unresolved and the perception of bias in favor of Moose Jaw persisted, Liberty withdrew from the semifinals entirely.

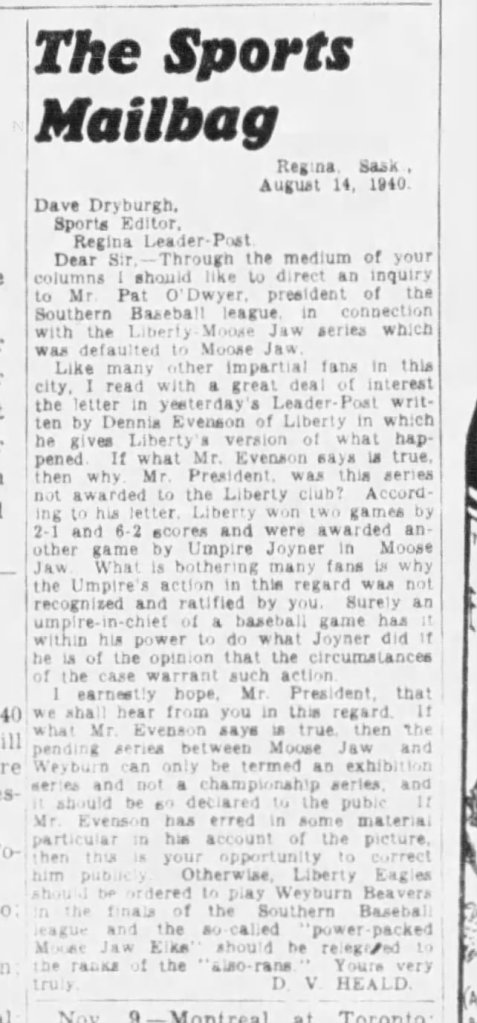

Problem Five: Fans Notice Discrepancies

Fans couldn’t help but detect a strong Moose Jaw bias in the newspaper coverage. This article questions why Pat O’Dwyer overruled the original umpire’s call in Game Two and why the Liberty club was subjected to such poor treatment.

O’Dwyer Responds

In his response, Pat O’Dwyer pointed to Rule 60, which allows an umpire to change his mind, noting that had Liberty left the field, the game would have been awarded to them. He referenced a conversation between the managers but admitted he could not verify its accuracy. Scheduling quickly became contentious: Moose Jaw claimed it could not play on Wednesday, contradicting earlier arrangements, and notified Liberty, through O’Dwyer, that they would play on Thursday. O’Dwyer sent a telegram to Liberty requesting them to acknowledge the Thursday game. After not receiving a reply by Wednesday, O’Dwyer finalized and published the game dates and locations. Liberty discovered, via the newspaper, that their Wednesday game had been moved to Thursday and a deciding Game Five would be played in Moose Jaw. Liberty later claimed the forfeited game, and after a tense telephone exchange, the team withdrew from the competition entirely.

O’Dwyer’s explanation feels more procedural than appeasing, leaning on the letter of the rules while sidestepping the optics of fairness. By locking in and publicizing the schedule before Liberty’s response, he created the impression—fair or not—that Moose Jaw’s needs were prioritized. The inability (or unwillingness) to verify the managers’ conversation leaves a gap in the narrative, and the sequence of events suggests that communication breakdown, rather than inevitability, escalated the dispute to Liberty’s withdrawal.

Weyburn Beavers are the Winners

Moose Jaw advanced to play Weyburn and were beaten.

Final Thoughts

The 1940 season ended under a cloud of controversy, Liberty’s playoff exit leaving lasting bitterness. The baseball I won at auction, bearing the inscription Winners of the Southern Baseball League, might have been more than a simple souvenir; it could have been a quiet act of protest, a way for the players to claim the victory they believed was theirs. One can imagine it passing from a “G.W. (or J.W.) Johnson” in Texas to a steadfast fan who supported the Eagles until the very end—a story of pride, resilience, and the enduring bond between a team and its community.

Amid the turmoil, Liberty’s 1940 roster still boasted remarkable talent, with players and a manager whose skill and leadership shone through the turbulence. Their contributions on the field and their place in the larger story of prairie baseball deserve recognition beyond the dispute that ended their season.

As with the orphaned photographs I studied as part of my master’s thesis research, this baseball had been separated from its original context, its meaning suspended. But stories have the power to reactivate what time seems to erase, breathing new life into objects, restoring their voices, and reconnecting them to the histories they once carried. In telling the Liberty Eagles’ story, this ball is no longer just cork, hide, and stitching; it is a living artifact, speaking again of a summer when a team, a community, and their dreams took the field together. When I look at it on my shelf, I will forever think of this story. Man, I love what I do!

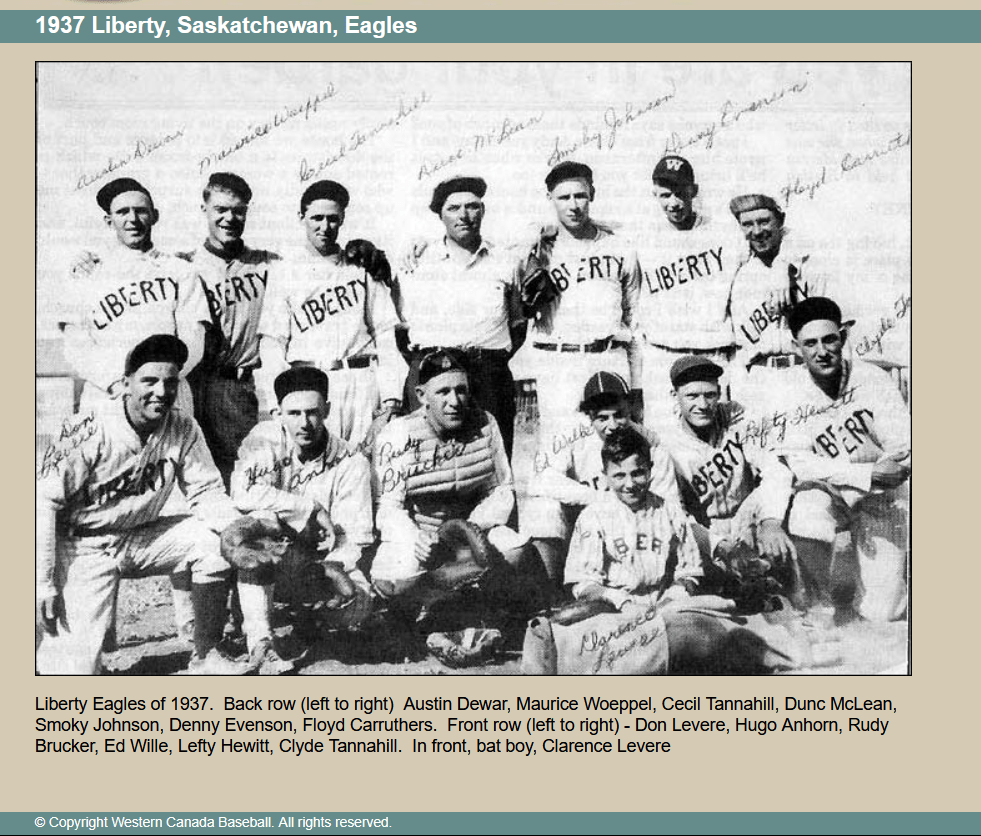

Extra Inning: Notable Liberty Eagles

Featured Player: Cecil Tannahill

The story of Cecil Tannahill and his family mirrors that of many American families who moved north to Western Canada in the early 1900s, bringing their love of baseball with them. Cecil Tannahill was born on December 12, 1912, in a sod house and grew up on the prairies, learning the rhythms of farming, small-town community life, and playing baseball.

In later years, Cecil moved to Regina, where he worked for the Robert Simpson Co. Ltd. Beyond his professional life, he became a passionate collector of trade tokens, paper money, and other pieces of Saskatchewan’s past. Over more than two decades, he gathered more than a thousand items, donating much of his collection to the Saskatchewan Department of Culture and Youth so that it could be shared with people across the province. (“Obscure, forgotten items in trade token collection”) His leadership matched his commitment to preserving local history as he served as the first president of the Regina Coin Club, fostering a community of collectors and historians dedicated to keeping Saskatchewan’s heritage alive.

Red Haley

Red Haley’s baseball journey spanned some of the most dynamic eras and leagues in the sport’s history. He made his Negro Leagues debut in 1928, splitting the season between the Birmingham Black Barons and the Chicago American Giants. Over the next several years, he showcased his versatility, throwing left-handed, batting right, and playing every infield position: first, second, third, and shortstop. Although primarily a second baseman, Haley was the kind of utility player every manager valued. (Riley 347) (“Red Haley Stats, Height, Weight, Position, Rookie Status and More | Baseball-Reference.com”)

After his early years with Birmingham and Chicago, Haley later suited up for the Kansas City Monarchs and the barnstorming Pollack’s Cuban Stars. In 1934, his career took him north to Bismarck, North Dakota, where semi-pro team owner Neil Churchill was assembling a powerhouse roster. Shortly after Haley’s arrival, Churchill signed Satchel Paige, adding the legendary pitcher to a lineup that already included Chet Brewer, Double Duty Radcliffe, Quincy Troupe, and Barney Morris. The integrated Bismarck Churchills dominated, winning the National Baseball Conference semi-pro championship in 1935.

Haley’s reputation as a long-ball hitter and adaptable infielder made him a sought-after player for barnstorming clubs during the 1930s. By the end of the decade, his career brought him to Saskatchewan, where he played for at least two seasons for the Liberty Eagles in 1939 and 1940, leaving his mark on prairie baseball history.

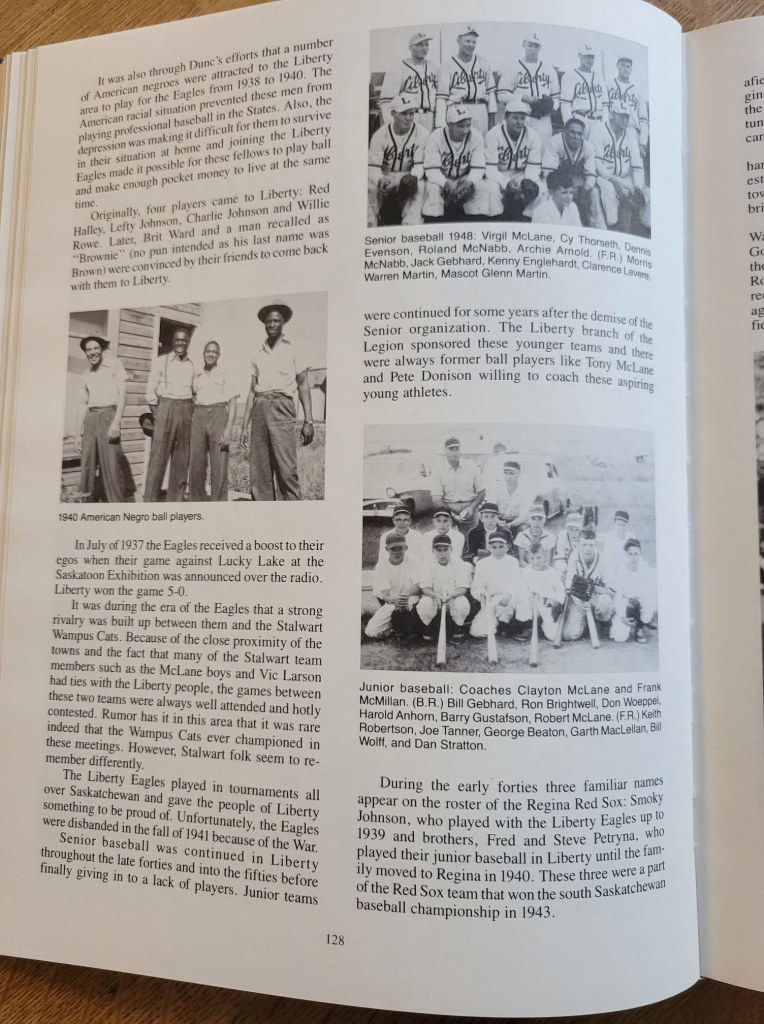

Unfortunately, the other African American players who were part of the team from 1938 to 1940 were not fully acknowledged by name in the Liberty History Book. (Larson et al. 109) Based on the signatures on my baseball, I have been able to identify the other 1940 players of African descent as Edward Brown, Britt Ward, and Lefty Johnson. In the book “Wheat Province Diamonds”, Hack and Shury identify additional players: Charlie Johnson and Wilie Rowe. (Hack and Shury 124)

Dunc Mclean

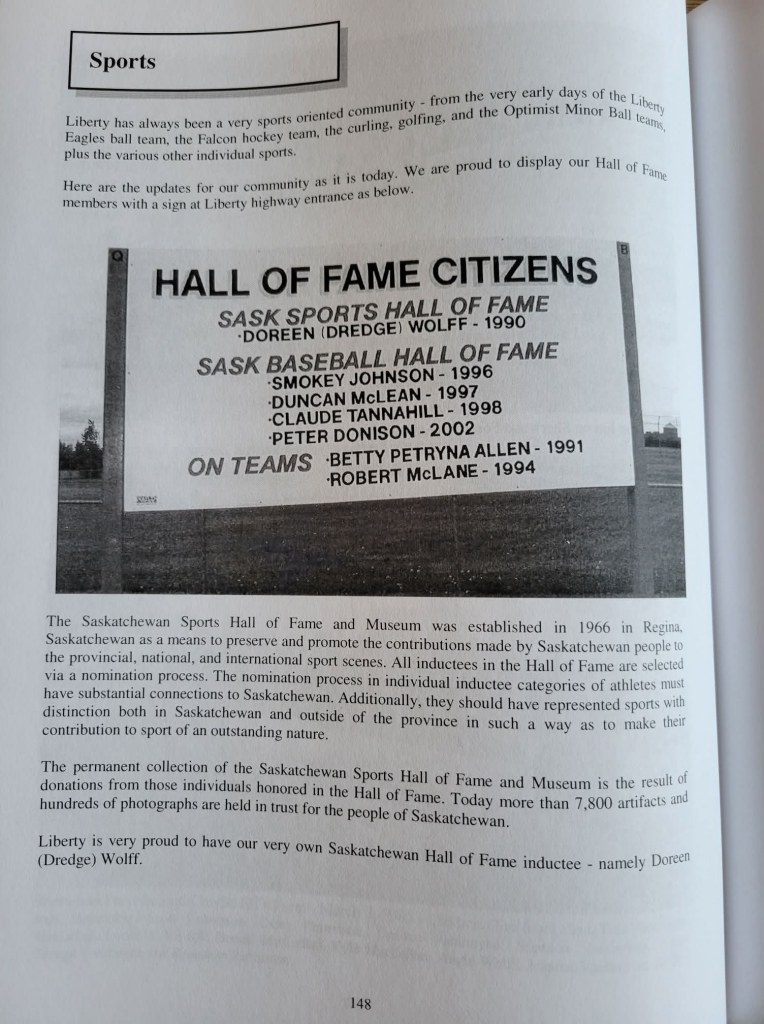

Dunc’s passion for baseball had taken on the role of coach and manager for the Liberty Eagles. McLean had a knack for recruiting talent, often striking up conversations with opposing stars and convincing them to don an Eagles uniform for the next game, famously embracing the strategy, “If you can’t beat them, get them to join you.” (McDade and Hutchinson 29–30) In 1937, his team claimed the Senior Ball Championship at the Saskatoon Exhibition, with the thrilling final broadcast on the radio. After relocating to Prince Albert in 1949, McLean played a key role in establishing the Minor Ball Association, serving as commissioner for two decades. He later guided the Prince Albert Bohemians to the Provincial Championship in 1968. With more than 40 years in the sport, his leadership and dedication left a lasting mark on Saskatchewan baseball, culminating in his induction into the Saskatchewan Baseball Hall of Fame in 1997. (McDade and Hutchinson 29–30)

1940 Game Reports

https://attheplate.com/wcbl/1940_50i.html

More Baseball Images

Unexpected Discovery

I was at the Saskatchewan Baseball Hall of Fame Induction just this past weekend, and I took some time to go through their image library. Lo and behold, I found a 1940 team photo that included the four African-American players! I can make out three of them: Back, second from left is “Johnson”. Back, far right is Red Haley. The second right is Edward Brown. In the front, far left, I cannot identify. What an incredible find.

1940 Liberty Eagles Roster : Brown Edward UT/SS, Brucker Rudy C/OF, Crooks Hugh RHP/OF (also Notre Dame), Demers 3B, Evenson Denny 3B/P, Haley Red 2B, Jisson OF, Johnson Lefty LHP/1B, Johnson J.W., Johnson Bill(Smoky) P/OF, Lane OF, Larson Vic 1B, Lee 2B, Levere Eldon SS, Martin 1B, McLean Duncan MGR, McLane P/OF, McNab OF, Pelac OF, Roney Bill, OF, Tait/Tate C/OF, Tanahill Cecil OF, Tanahill, Clyde, Ward Brit OF, Wille Eddie 1B, Woeppel Morris OF

Baseball Community Adds More Information

After I posted my article on Historic Saskatchewan, a Facebook page dedicated to sharing local history, Connie & Kelvin Drimmie reached out to me. They provided some additional information from another Liberty history book called “Early Days to Modern Ways”. It included another image of the African American Players as well as a list of Liberty player inductions into the Saskatchewan Sports and Baseball Halls of Fame. Thank you, Connie and Kelvin!

References

1937 Liberty Eagles. attheplate.com/wcbl/1937_1g2.html.

Dempson, Pete. “Pick Your Star: Mythical Ball Team Is Selected.” The Leader Post, 10 Aug. 1940, p. 13.

Evenson, Dennis. “Liberty’s Angle: More On The Withdrawal Of The Eagles.” The Leader Post, 13 Aug. 1940, p. 13.

Hack, Paul, and Dave Shury. Wheat Province Diamonds: A Story of Saskatchewan Baseball. Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame, 1997.

Heald, D. V. “The Sports Mailbag.” The Leader Post, 15 Aug. 1940, p. 13.

“History of the RCC | the Regina Coin Club.” The Regina Coin Club, http://www.reginacoinclub.ca/history-of-the-rcc.

J.D. Mah, et al. “1935 Bismark Team.” attheplate.com, http://www.attheplate.com/wcbl/1935_1g.html.

Larson, V., et al., editors. Fifty Years of Liberty 1901-1955: dedicated to the Pioneers of the Liberty District. 1955.

“Liberty Drop Out of Baseball: Moose Jaw Elks Advance Into Finals.” Moose Jaw Times Herald, 8 Aug. 1940, p. 6.

“Liberty Out of Series.” The Leader Post, 8 Aug. 1940, p. 1.

Mah, J. D., and Rich Necker. “1937 Liberty, Saskatchewan, Eagles.” attheplate.com, http://www.attheplate.com/wcbl/1937_1g2.html.

McDade, Lois, and Jean Hutchinson. “Hall of Fame: Dunc Mclean.” Saskatchewan Historical Baseball Review by the Saskatchewan Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum Assoc., 1997, pp. 29–30.

“Moose Jaw Elks Advance Into Finals.” Moose Jaw Times-Herald, 8 Aug. 1940, p. 6.

“Obscure, forgotten items in trade token collection.” Star Phoenix, 21 Oct. 1974, p. 4.

O’Dwyer, Pat. “The Sports Mailbag.” The Leader Post, 19 Aug. 1940, p. 13.

O’Dywer, Pat. “Liberty Tosses in Towel!” The Leader Post, 9 Aug. 1940, p. 21.

“Red Haley Stats, Height, Weight, Position, Rookie Status and More | Baseball-Reference.com.” Baseball-Reference.com, http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/h/haleyre01.shtml.

Riley, James A. The Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Leagues. Carroll and Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994.

“Rings Given Ball Team.” The Leader Post, 17 Sept. 1940, p. 16.

“Rings Given to Ball Team.” The Leader Post, 17 Sept. 1940, p. 16.

Southern Sask Baseball League UpComing Season Details. The Leader Post, 6 May 1940, p. 16.

“Umpire Took the Proper Action.” Moose Jaw Times Herald, 5 Aug. 1940.

Dunc Mclean was my great Grandfather, my grabdmother, Lois mcdade was instrumental in getting him inducted after he passed into the sask baseball hall of fame. i was their at his induction in 1997. Grandma lois passed away this January, she would have been proud to read the legacy of out home town liberty eagles still lives on. Such a great and amazing story

LikeLike

Hi Jonathan, I’m so glad you found the story. There is such a rich baseball history in Saskatchewan, and it’s people like your Great Grandfather that helped shape and define it. You should be very proud of his legacy.

LikeLike