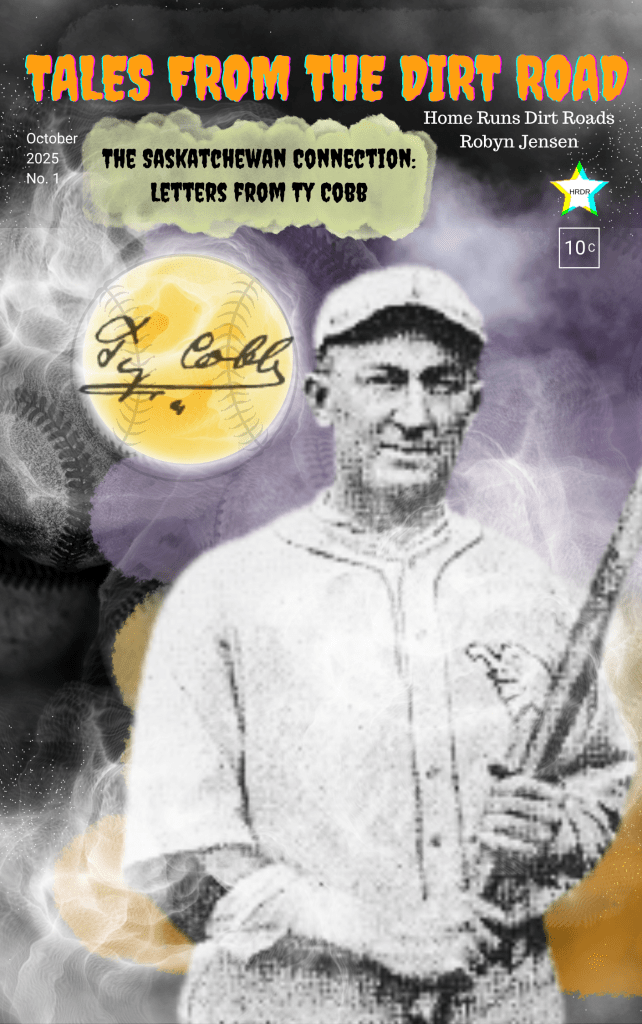

The Saskatchewan Connection: Letters from Ty Cobb

Every October, I like to pull a story that feels a little haunted—not by ghosts exactly, but by questions or unknowns that still echo through time.

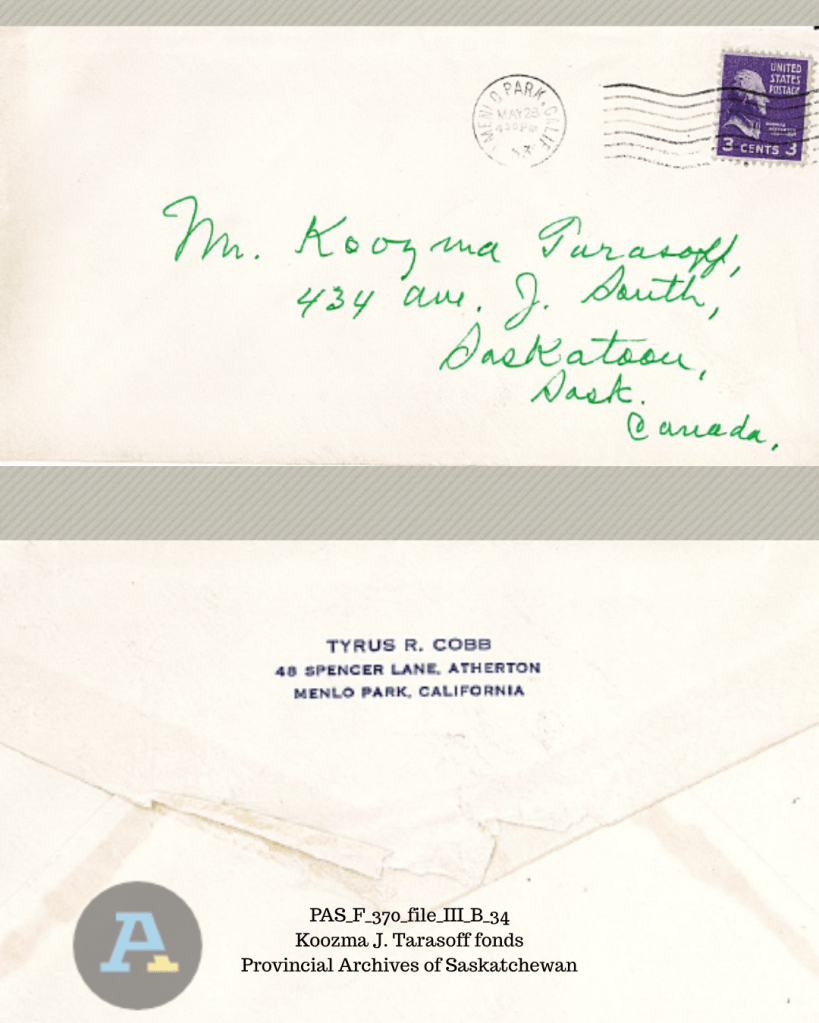

This year’s mystery begins at the Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan with one of the most unlikely connections in local baseball history: a teenage boy from Saskatoon, Koozma Tarasoff, and the legendary Ty Cobb, a controversial but brilliant player whose name continues to spark debate decades later.

How did one of the most infamous, fiery figures in baseball end up corresponding with a young Saskatchewan kid living thousands of miles away? What did they talk about?

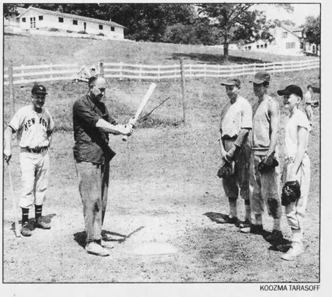

The trail leads back to the Ozark Baseball Camp, summer of 1952, where Cobb was hired as a guest instructor. Tarasoff was there, a teenager who had come all the way from Saskatchewan to learn. Something about his focus, his drive, maybe his curiosity, caught Cobb’s attention. When the camp ended, Cobb didn’t just sign a ball and move on. He started writing letters to Koozma.

Letters that lasted about two years carried advice, baseball ‘how-to’ manuals, and even an invitation to try out with the Hollywood Stars in California.

It’s a story about private mentorship and mystery, how baseball’s fiercest competitor may have found something familiar in a young player from the prairies. During the same time, the public saw the most recognized side of Ty Cobb: the volatile figure newspapers called a “dirty player” and “nuts” (The Independent, March 12, 1952, 18). Cobb was indeed a difficult man who once said he had to fight for everything he achieved in baseball. The game had hardened him, building an emotional wall and armour of arrogance around one of its greatest players. Yet in his letters to Koozma Tarasoff, that armour seems to crack. Here, Cobb writes not as the legend or the fighter, but as a man stripped of performance, a mentor revealing a rare vulnerability, wanting only the best for a kid who reminded him what the game once meant.

So this Halloween, pull up a chair and open those letters and see what the ghost of Ty Cobb has to say. Cobb’s career ended almost a century ago, so let’s briefly revisit his life and times.

Who was Ty Cobb?

Tyrus Raymond “Ty” Cobb (1886–1961) is often remembered as both a genius and a paradox of baseball’s early years. Born in rural Georgia, Cobb rose from small-town sandlots to become one of the most dominant players in the history of the game. Over a 24-year major-league career, 22 of them with the Detroit Tigers, he set more than 90 records, including a lifetime batting average of .366, which still stands as the highest in Major League Baseball history. Known for his fierce competitiveness, Cobb captured 11 batting titles, won the 1909 Triple Crown, and redefined base running with a blend of intelligence, aggression, and audacity that electrified fans and intimidated opponents.

Yet Cobb’s importance to baseball goes beyond statistics. He embodied the raw edge of the early 20th-century game, the dirt, the daring, racism, and the psychological warfare that shaped what historians now call the “Deadball Era.” His reputation was complicated: admired for his skill but vilified for his temper and intensity. To some, he was baseball’s first superstar; to others, its first villain. Still, his influence was undeniable. Cobb’s influence runs through the DNA of baseball itself. His style of play — fierce, strategic, and fearless — set a template for how players approach competition and intensity even today. (Daniel Ginsburg, “Ty Cobb,” BioProject)

Cobb meets Koozma at the Ozark Baseball Camp — Where the Story Begins.

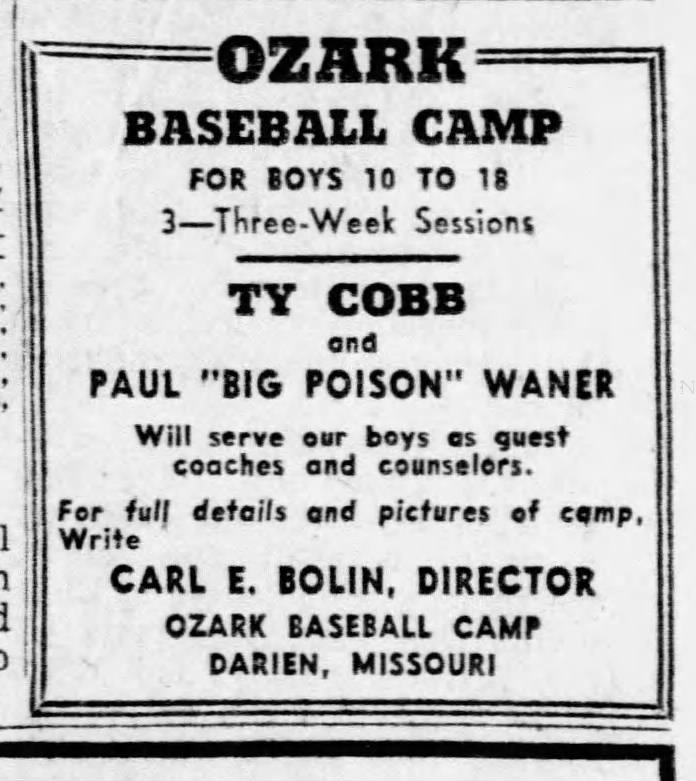

In June 1952, Ty Cobb, now 66, stepped back into baseball —this time not to play, but to teach. He joined director Carl Bolin’s coaching staff, which included former St. Louis Cardinal first baseman Jim Bottomley, Boston Braves pitcher Ben Cantwell, New York Yanks’ twirler Wally Schang, and Pittsburgh moundsman Elmer Jacobs. New to the summer staff were Pirates’ former slugger Paul “Big Poison” Waner and Ty Cobb. The Ozark Baseball Camp, a Missouri summer program for boys eager to learn the game from the greats (Arlington Heights Herald, June 13, 1952, p.20). The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that Cobb was still fierce, demonstrating slides, leads, and the art of controlled aggression on the bases (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 15, 1952, p. 66).

Among the campers was a teenager from Saskatchewan, Koozma Tarasoff, an outfielder, who had travelled south to soak up every ounce of instruction he could. Something about the boy’s focus must have caught Cobb’s eye. When the camp ended, Cobb and Tarasoff forged a friendship through letter writing.

Ty Cobb is holding the bat, and Koozma is standing third from right.

What began as a polite note of gratitude from Koozma became the start of an improbable mentorship through the mail sent back and forth across the border.

Ty Cobb — Public and Private

Ty Cobb’s relationship with baseball—and with himself—was shaped as much by hardship as by triumph. When he entered the major leagues in 1905, the teenager from Georgia arrived still carrying the weight of tragedy: his father had been shot and killed by his mother only weeks earlier. Thrust into a northern clubhouse for the first time, he was met not with sympathy, but suspicion and ridicule. His Detroit teammates made him the target of cruel hazing, cutting up his bats, ruining his caps, and mocking his accent. The isolation that followed hardened him. It taught him that survival in baseball, as in life, meant fighting for everything you wanted. That early humiliation built some of the armour he would wear for the rest of his career.

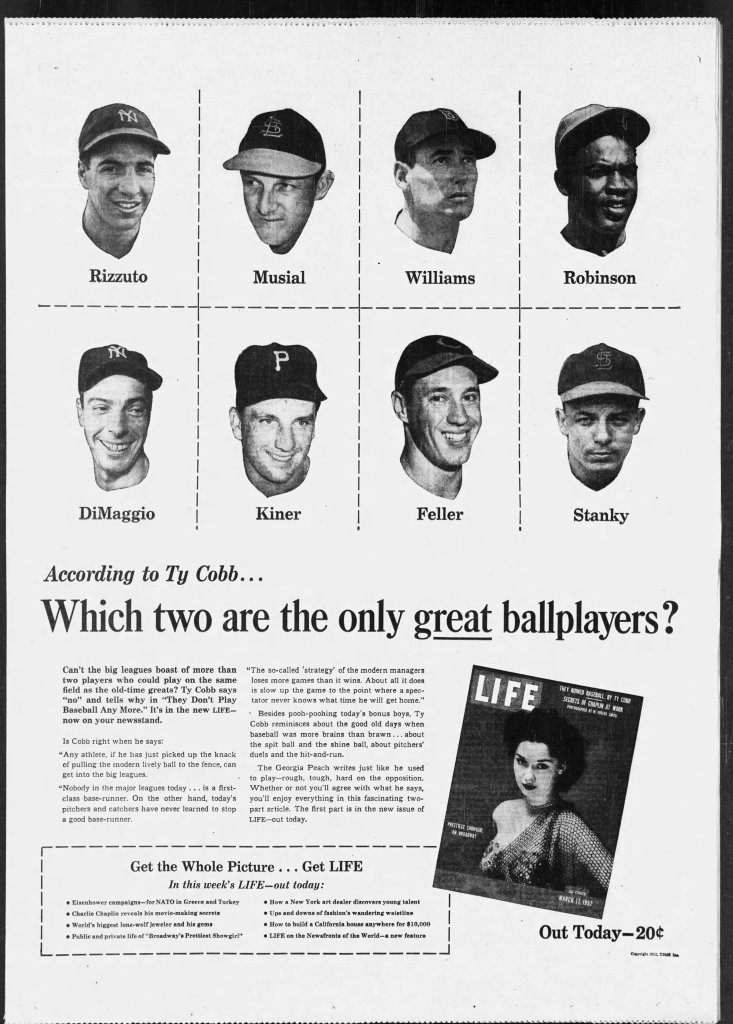

Nearly five decades later, in 1952, the world was once again talking about Ty Cobb—and not kindly. Life magazine had just published his series of articles in which he boldly ranked baseball’s greatest players, beginning with “Who Was the Greatest Player?” where Cobb, never one to shy away from controversy, placed himself above Robinson, DiMaggio, and the rest (The Daily Worker, March 24, 1952, p. 3).

The reaction was swift and unforgiving. Papers from Chicago to Portland accused him of bitterness and self-importance. The Sunday Oregonian called him “brilliant but bitter” (Sunday Oregonian, June 8, 1952, p. 41). Lester Rodney, writing in the Daily Worker, described Cobb’s later article, “They Don’t Play Baseball Any More,” as arrogant and “baloney-loaded,” criticizing the 66-year-old Georgian’s attacks on modern players like Joe DiMaggio, Jackie Robinson, and Roy Campanella. Rodney argued that Cobb’s contempt for the postwar game and his dismissive remarks about Black ballplayers revealed how deeply he remained tethered to the prejudices and hierarchies of his own era (Daily Worker, March 14, 1953, 25).

But beneath the bravado of those Life essays was something more complicated. By then, Cobb had long been defending the style of baseball he believed the modern game had abandoned—the precise, strategic play of the Deadball Era. He mocked what he saw as the new “swing-crazy” generation of hitters and mourned the loss of the tactical, mental side of the sport that had once defined his greatness. As the Baseball Hall of Fame later observed, these writings revealed not just ego but a man trying to hold on to a version of the game—and of himself—that was disappearing. (Rothenberg, Matt. “Shortstops: Letters from Ty Cobb.”)

Cobb still believed baseball was a thinking man’s game. He wrote about discipline, focus, and nerve—the same principles he once embodied between the lines. And while the world saw only the crusted arrogance of a legend past his time, his letters to people like Koozma Tarasoff tell a different story: that behind the armour was a man who could still care deeply, teach patiently, and reveal a softer side rarely seen by the public.

While the public debated his ego, behind the scenes Cobb was quietly writing to a young Canadian—offering encouragement, tactical notes, and even annotated instructions mailed north to Saskatchewan. This was the private Cobb: precise, reflective, and unexpectedly generous with his knowledge, passing along the game’s lessons to someone he believed might carry them forward.

The Letters and the ‘How-To’ books, 1952 & 1953

The letters between Ty Cobb and Koozma Tarasoff are striking for their warmth, candor, and practical depth, a glimpse into the private world of a man better known for his temper than his tenderness. In them, Cobb speaks as both craftsman and coach, his tone alternating between tough-minded precision and paternal encouragement.

It’s a beautiful thing to read. In one letter, written while recovering in the hospital from what he called “exhaustion from baseball commitments,” Cobb sounds weary yet vulnerable, confiding in the young player about the toll the sport had taken on his body and mind. Moments like these strip away the myth of the Georgia Peach and reveal a man reflective about his own limits and the demands of baseball.

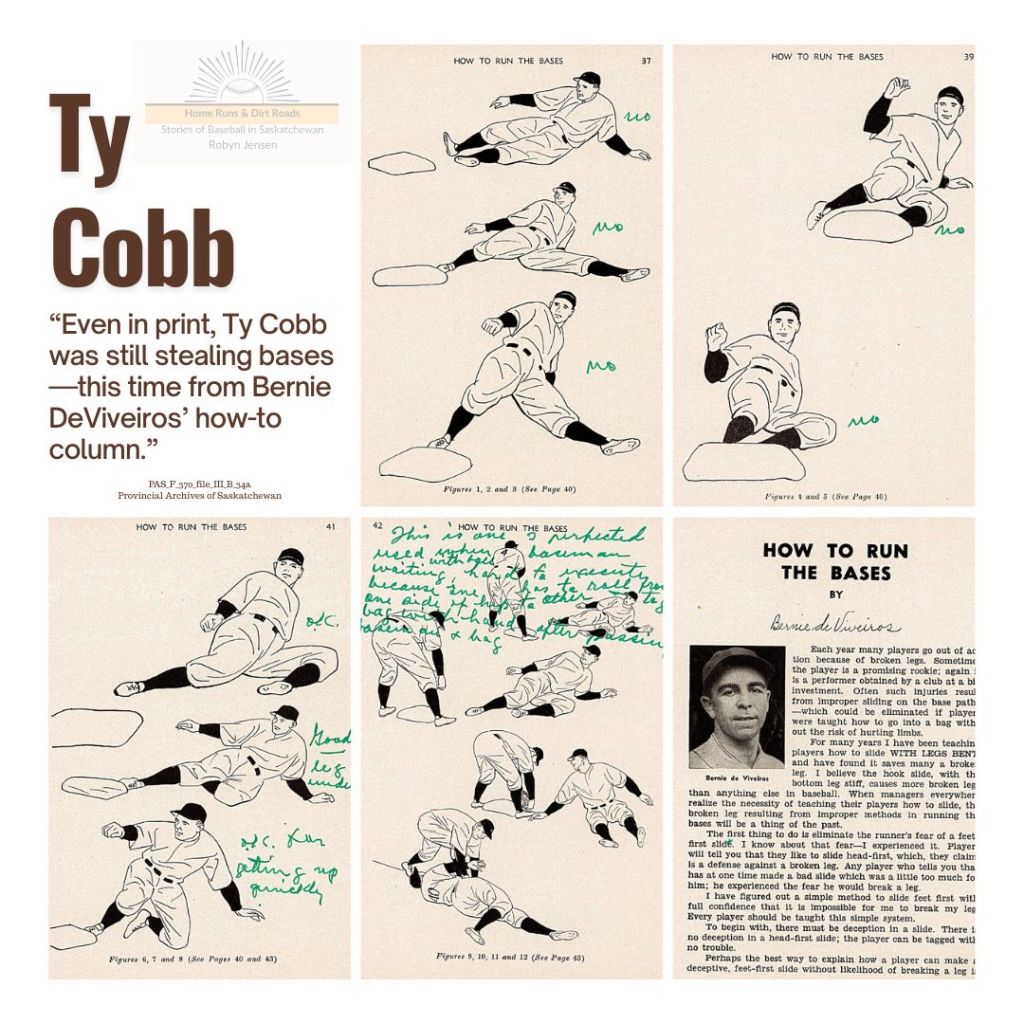

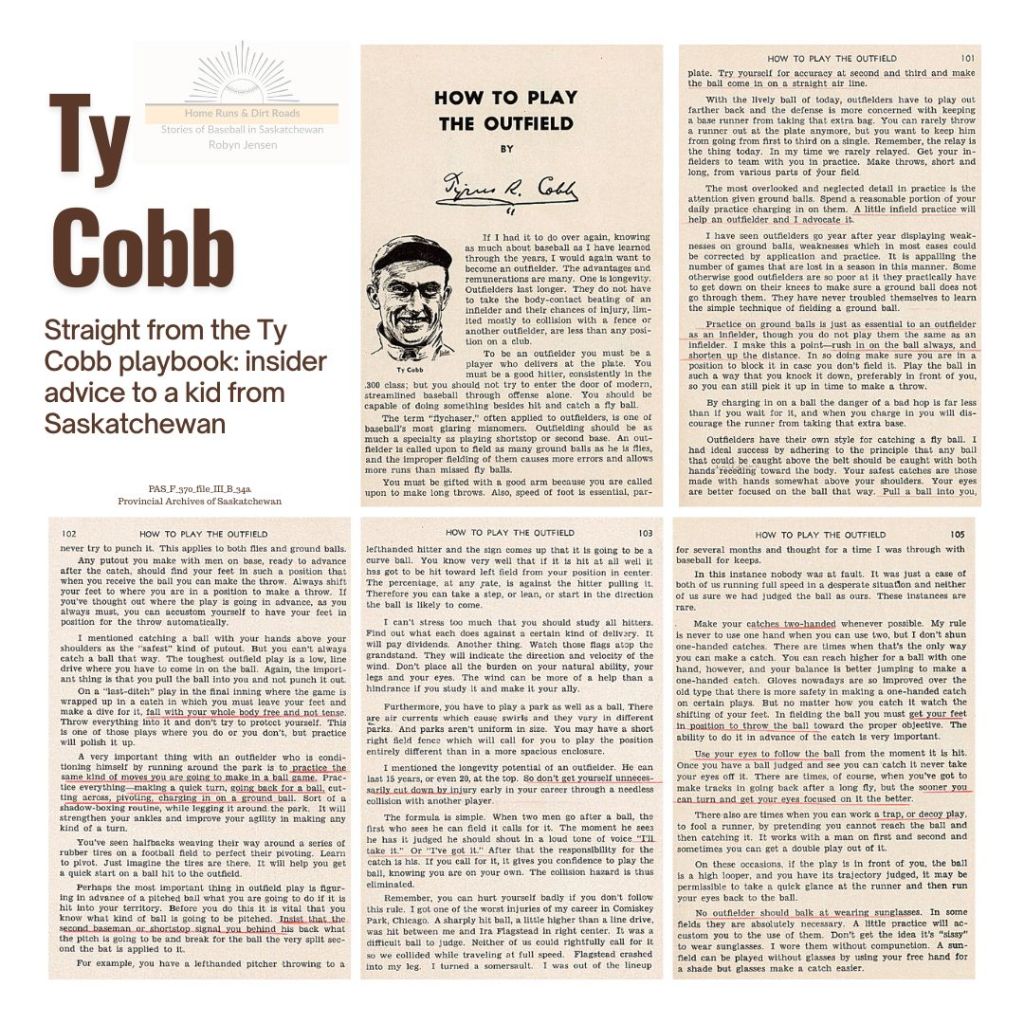

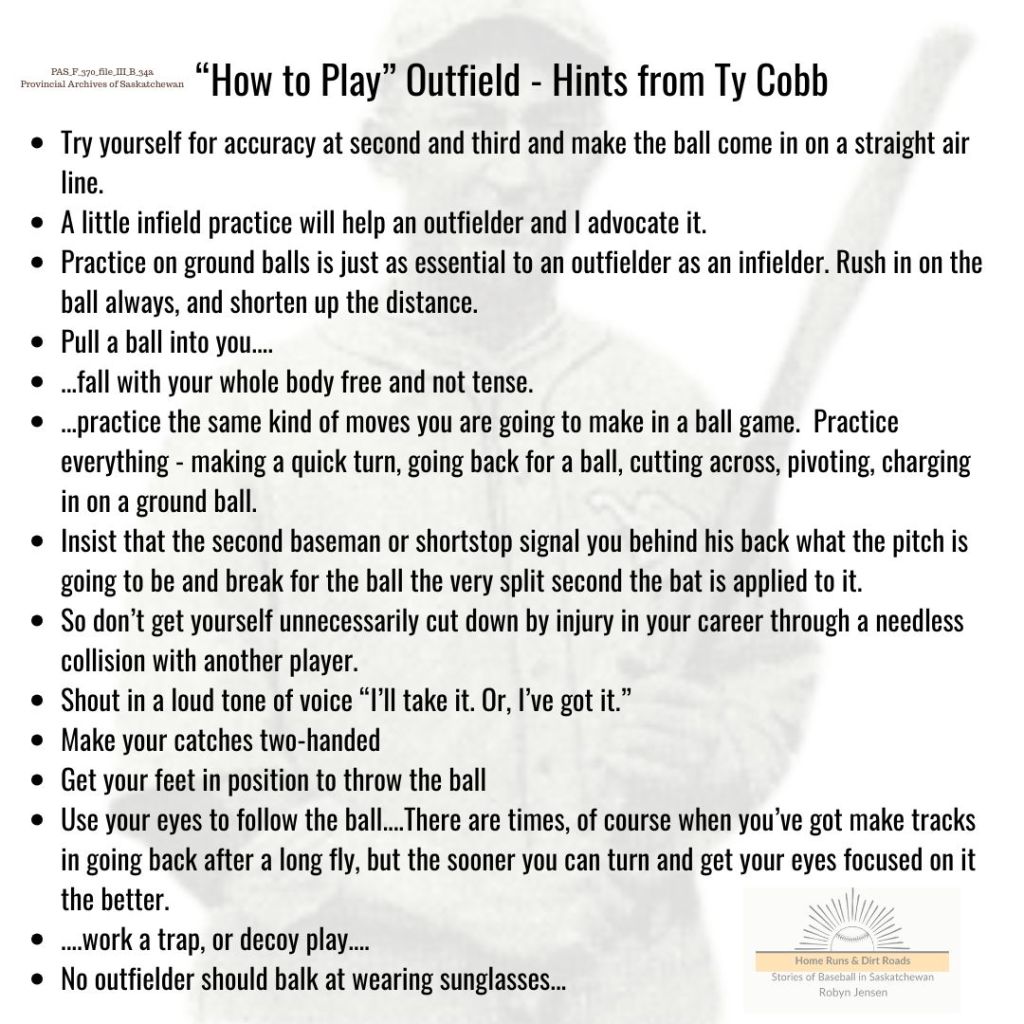

Other letters are dense with instruction. Cobb describes how to make a homemade slide guard from sheep’s wool and quilted silk cloth, or “sateen,” to protect the hip and thigh during practice — a small but telling example of his characteristic ingenuity. He sent Tarasoff four baseball how-to manuals, some carefully annotated or important sections underlined in red with his own hand. In the margins, Cobb added practical hints and personal reflections, transforming ordinary coaching pamphlets into living documents of his baseball philosophy — part textbook, part testament.

Most of his advice drew on lessons he had already written about over the years, with one notable exception: a passage he borrowed from fellow Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby, emphasizing the importance of confidence.

Cobb didn’t hesitate to challenge other instructors, either. In Bernie DeViveiros’ chapter on How to Run the Bases, the neatly printed diagrams are interrupted by Cobb’s scrawled corrections and emphatic interjections — “No, no, no!” — as if the old master were still shouting from the coach’s box, unwilling to let any point go unclarified. (See Appendix A -Cobb’s Advice)

These letters reveal a rare tenderness beneath Cobb’s fierce exterior—the mentor’s voice that would soon extend beyond the page, guiding a young Saskatchewan ballplayer on an unforgettable journey.

Koozma’s Memories

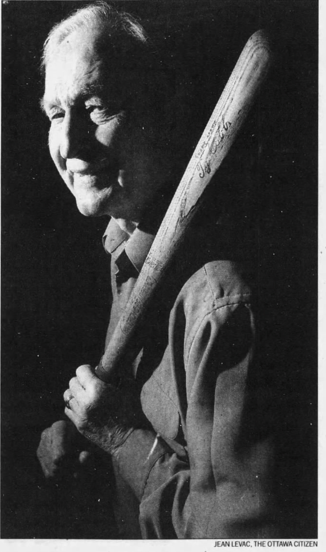

As recounted decades later in The Star-Phoenix, The Ottawa Citizen, and The National Post (2004), Koozma Tarasoff remembered both the excitement of that journey and the man who awaited him at its end.

In February 1953, the Saskatoon community gathered at the airport to send off “Cobb’s protégé.” Before reporting to the Hollywood Stars’ spring training camp in Anaheim, Tarasoff was scheduled to spend several days at Ty Cobb’s home in Menlo Park, California, for “special instruction” from the Georgia Peach himself (Star-Phoenix, February 26, 1953, p. 21). That farewell, captured in a photograph of Koozma standing with his parents and local supporters, symbolized the reach of Cobb’s mentorship and the extraordinary journey of a young Saskatchewan boy whose dream had carried him into baseball’s golden age.

When Tarasoff arrived in California, Cobb welcomed him into his home and took him under his wing. The young ballplayer remembered how Cobb would take him out for ice cream, share stories from his playing days, and offer lessons that blended psychology with technique. During this visit, Cobb sat down, rolled up his pant leg, and revealed the truth beneath his legend—a limb crosshatched with scars from years of slides, spikes, and collisions. “Out came his leg, criss-cross cut like a thatched roof,” Tarasoff recalled (Ottawa Citizen, December 26, 2004, 35). The sight was startling: the physical toll that underpinned Cobb’s perfectionism. In that quiet moment, the myth fell away. Cobb wasn’t performing or competing; he was confessing, showing the cost of a lifetime spent fighting to stay on top.

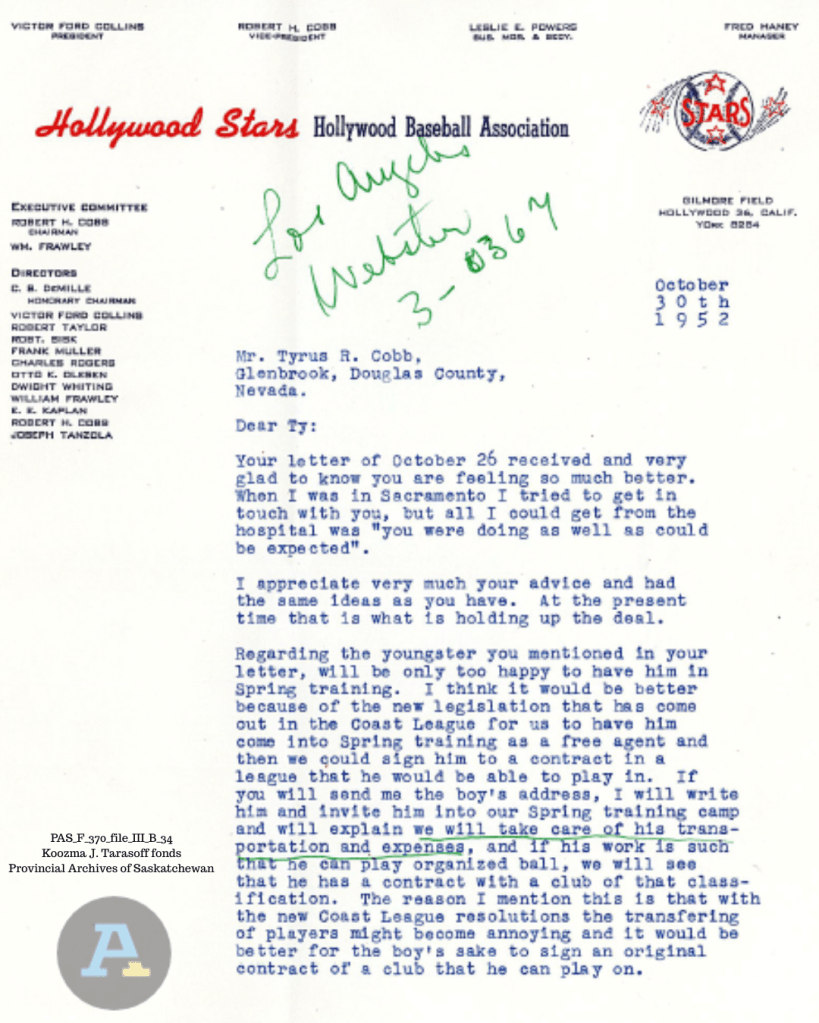

Cobb’s belief in Tarasoff’s potential went beyond mentorship. He personally arranged an all-expenses-paid tryout with the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League, contacting manager Fred Haney to ensure Tarasoff would be given a fair look. The tryout included an exhibition game that featured two legends—Satchel Paige and Ted Williams—and Cobb himself came to watch, proud and anxious to see how his student would perform among professionals (National Post, December 27, 2004, S10).

But Tarasoff, arriving from the frozen Saskatchewan winter, was at a disadvantage. The months of snow had left him unpracticed and stiff, a contrast to the seasoned players from warmer climates. Cobb, ever the perfectionist, was disappointed but still encouraging. In a letter that followed, he offered the young Canadian blunt advice and a fatherly challenge:

“Now if you want to play baseball, then get with any club, amateur, semi-pro or what not, where you can play a lot of baseball—and if you fail there, then forget it all and go for something else.”

Though Tarasoff never made the professional ranks, the experience marked him for life. The chapter of letters and baseball may have closed, but its lessons endured. Cobb’s belief in discipline, perseverance, and integrity stayed with Koozma long after his brief brush with professional baseball. The mentorship that began with a few handwritten pages evolved into a deeper philosophy of purpose—one that would later inform his work as a writer, researcher, and advocate for cultural understanding. The young ballplayer from Saskatchewan, once coached by a baseball legend, would carry those same values into the fields of peace and heritage.

Koozma – After Baseball

Koozma Tarasoff’s story did not end on the diamond. Born February 19, 1932, near the Doukhobor community of Pokrovka, Saskatchewan, he was the son of John and Anastasia Tarasoff, and the grandson of a Doukhobor leader who took part in the historic “burning of firearms” protest in Russia in 1895. His family moved to Saskatoon in the 1940s, where both Russian and English shaped his upbringing.

After his correspondence with Ty Cobb, Tarasoff’s curiosity turned toward culture, peace, and identity. From 1953 to 1958, he edited and published The Doukhobor Inquirer (later The Inquirer), fostering dialogue among young Doukhobors. He went on to earn degrees in English, Psychology, Philosophy, and Sociology from the Universities of Saskatchewan and British Columbia.

Over the next decades, Tarasoff became a respected researcher, consultant, and writer on multiculturalism and Doukhobor heritage. His 2002 book Spirit Wrestlers: Doukhobor Pioneers’ Strategies for Living captures the philosophy that guided his life — one rooted in peace, dialogue, and the preservation of cultural memory. (Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan, Koozma J. Tarasoff Fonds, F 370)

Appendix A – Cobb’s Advice

Bibliography

Arlington Heights Herald (Arlington Heights, IL). “What Is the Ozark Baseball Camp?” June 13, 1952, p. 20.

Calgary Herald (Calgary, AB). “Cobb Protégé.” September 7, 1956, p. 22.

Cam’s Corner. Star-Phoenix (Saskatoon, SK). By Cam McKenzie. November 14, 1952, p. 25.

Daily Worker (Chicago, IL). “Ty Cobb Life Magazine Article.” March 24, 1952, p. 3.

———. “More on Ty Cobb.” By Lester Rodney. March 14, 1953, p. 25.

Ginsburg, Daniel. “Ty Cobb.” BioProject – Person. Society for American Baseball Research. January 4, 2012. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ty-cobb/

National Post (Toronto, ON). Kevin Mitchell. “The Ty That Binds.” December 27, 2004, p. S10.

Ottawa Citizen (Ottawa, ON). Kevin Mitchell. “The Sweet Side of Ty Cobb.” December 26, 2004, p. B11.

Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan. Koozma J. Tarasoff Fonds. F 370. Biographical sketch in finding aid. Regina: Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan.

———. Koozma J. Tarasoff Fonds. PAS F 370, file III B 34a.

Rothenberg, Matt. “Shortstops: Letters from Ty Cobb.” Baseball Hall of Fame. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/short-stops/letters-from-ty-cobb

Star-Phoenix (Saskatoon, SK). Kevin Mitchell. “Ty Cobb: The Man No One Knew.” December 24, 2004, p. B2.

———. “Cobb’s Protégé Gets Sendoff.” February 26, 1953, p. 21.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch (St. Louis, MO). “Ty Cobb at Ozark Baseball Camp.” June 15, 1952, p. 66.

Sunday Oregonian (Portland, OR). “How Right Were Ty Cobb’s Criticisms?” June 8, 1952, p. 41.