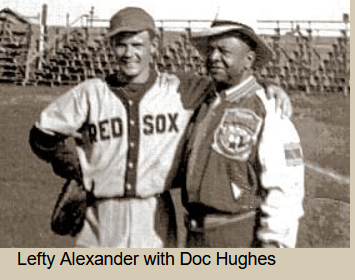

When Luther “Doc” Hughes arrived in Saskatchewan in 1911, he entered prairie sport through a role that offered access without equality. Brought to Saskatoon by J. F. Cairns to work with the Saskatoon Quakers, Hughes was initially employed as a groundskeeper and trainer, a masseur by trade, as later profiles would describe him. It was a position of intimate trust. Hughes tended to injured bodies, managed recovery, and worked behind the scenes in locker rooms and training spaces, gaining proximity to athletes and sporting institutions while remaining firmly outside formal authority.

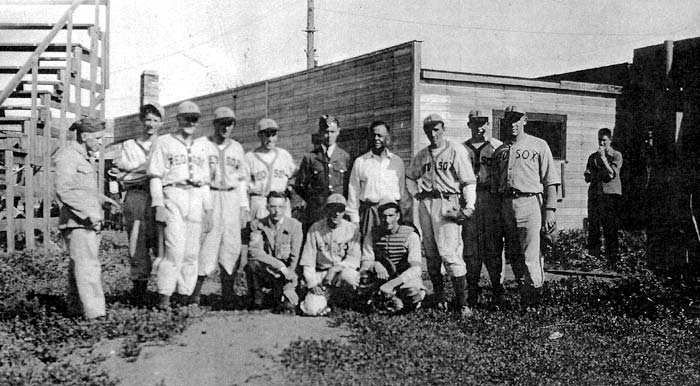

For an African-descent man in early twentieth-century Saskatchewan, this was a familiar pattern. Service roles provided entry into white-dominated institutions, but advancement beyond them was neither assumed nor guaranteed. What distinguishes Hughes is that he did not remain confined to this position. Over the next four decades, he systematically expanded his presence in prairie sport, moving from bodily labour into leadership and promotion. He opened gyms, organized boxing matches, trained athletes across baseball, hockey, football, and rugby, and eventually became the long-time manager and driving force behind the Regina Red Sox, a role he held for roughly fifteen years, shaping junior and senior baseball as well as community sport well into the postwar period.

This transition, from proximity to power, from service to supervision, was rare, and it was not universally welcomed.

Contemporary media makes that tension visible. In 1920, the Saskatoon Daily Star published a cartoon depicting Hughes kneeling in exaggerated prayer, rendered through racial caricature rather than sporting respect. The image reduced a respected trainer and promoter to spectacle, attempting to contain him visually at the very moment he had begun to exceed the role originally assigned to him. The cartoon did not question Hughes’s competence; it questioned his place. Its discomfort was not with his work, but with his authority.

That same unease surfaces in the uneven manner in which Hughes appears in police and court reporting. During the Prohibition era, newspapers repeatedly placed him in police court columns, most often in connection with liquor charges. In 1923, Hughes was held in police custody while awaiting trial for allegedly selling alcohol, a charge common among working-class entrepreneurs operating in public venues during this period. Earlier accounts document a 1917 charge related to alcohol sales on exhibition grounds that was ultimately dismissed after an extended argument. These encounters reflect routine contact between early prairie policing and informal economies rather than a singular narrative of criminality.

Other fragments appear more obliquely. In 1915, Hughes was charged with cruelty to an animal; the case was adjourned, and its resolution does not appear in surviving coverage. That same year, his name surfaces in connection with a police raid on a Saskatoon rooming house deemed disreputable by authorities. The article documents fines imposed on others but leaves Hughes’s precise role, whether owner, manager, or temporary caretaker, unclear. What these reports offer is not a complete account of wrongdoing, but a record shaped by surveillance: moments when Hughes became visible to the archive because of police attention. At the same time, the ordinary stability of his life went largely unremarked.

That stability, however, is documented elsewhere. Census records place Hughes in Ward 5, Saskatoon, as a homeowner, married to a white woman, Mary Molly Hughes, and affiliated with the Methodist church. This interracial household would have been highly conspicuous in the early 1920s. These domestic details complicate the police-column version of his life, revealing a man embedded in neighbourhood, property ownership, and faith, even as public scrutiny followed him.

In sporting pages, the contrast is stark. Hughes is quoted, trusted, and credited. He coached the Saskatoon Hilltops junior football team in the early 1920s, trained the Prince Albert Mintos in the 1930s, organized major boxing matches in Regina, and served as trainer for the Regina Rangers hockey team during their Allan Cup–winning 1940–41 season. He brought together baseball’s finest for the “Doc Hughes” Southern League All-Stars team which competed against barnstorming giants like the Cuban All-Stars and New Orleans Creoles. His Regina Red Sox teams won junior and senior championships and played in major-money tournaments, becoming a fixture of Saskatchewan baseball culture in the late 1930s, 1940s and early 1950s.

from attheplate.com

This trust extended beyond local recognition. In 1946, Hughes was interviewed by Baltimore Black journalist Herbert Frisby, who encountered him as a prominent and respected prairie sportsman, a figure whose authority was legible within African-descent transnational sporting networks even as it remained conditional at home.

Swipe to compare the before and after photo of Doc Hughes cleaned up by AI (Artificial Intelligence): The Leader Post, October 21st, 1952

After he died in 1952, that authority was gradually institutionalized. Awards bearing Hughes’s name were established (“Doc Hughes” Memorial Trophy for top pitcher), and by the late 1950s, 60s and 70s, he was publicly remembered as a foundational figure in Saskatchewan sport, a “real gentleman from Old Kaintuck,” as one obituary phrased it, drawing on the Kentucky identity Hughes himself often invoked in conversation, even as other records suggest he may have been born in Virginia. In 1996, Hughes was posthumously inducted into the Saskatchewan Baseball Hall of Fame. These commemorations smooth the rough edges of his life, celebrating endurance and contribution while leaving earlier tensions largely unspoken.

attheplate.com

Taken together, the record does not resolve Luther “Doc” Hughes. It reveals the conditions under which he lived and worked. He was hyper-visible in public life, scrutinized in police columns, caricatured in print, and yet deeply trusted within sporting institutions that depended on his skill, labour, and leadership. His life traces the narrow path available to Black professionals on the early twentieth-century prairies: entry through service, advancement through relentless competence, authority that was real but never entirely secure.

That Hughes nonetheless built institutions that outlived him, teams, leagues, and sporting cultures that carried on after his death, is not evidence of uncomplicated acceptance. It is evidence of navigation.

And that, ultimately, is his legacy.

Sources & Notes

This story was built from contemporary newspaper coverage, census records, and later retrospective writing. As with many early Black figures in prairie sport, Luther “Doc” Hughes appears most clearly in the archive at moments of public visibility, games, promotions, awards, and at moments of scrutiny, particularly in police and court reporting. Where records conflict or remain incomplete, those gaps are treated as part of the historical evidence rather than problems to be resolved.

Census Records

– 1921 Census of Canada, Saskatoon, Ward 5 (Polling Divisions 26–28), household of Luther Hughes and Molly Murray Hughes.

– 1931 Census of Canada, Saskatoon, listing Luther Hughes as a widower.

Newspapers

Saskatoon Daily Star

– “Charged with Cruelty to His Dog,” July 2, 1915.

– “Raid a House on 20th Street; Two Are Fined,” August 27, 1915.

– “Session In Inside Game Interesting,” Cartoon depicting Doc Hughes kneeling in prayer, September 1, 1920.

– Related coverage reflecting racialized portrayals of Hughes, September 1, 1920.

Star-Phoenix (Saskatoon)

– “Luther Hughes, Known in Sporting Circles as ‘Doc Hughes,’ Still in Police Cells,” July 11, 1923.

Leader-Post (Regina)

– “Doc Hughes, Prince Albert Liniment Expert,” May 18, 1934.

– “Hughes Sure He Has Goods: Doc to Stage Ambitious Fight Card,” October 1, 1936.

– “Banquet for Ball Winners: Doc Hughes’ Red Sox Take Junior Title,” October 22, 1938.

– “Doc Hughes’ Regina Red Sox Make Junior League Debut,” May 27, 1939.

– “Happy Birthday for Doc Hughes,” October 5, 1951.

– “Doc Hughes Award Presented,” October 21, 1959.

– “Doc Hughes Award Continues Sporting Legacy,” August 22, 1973.

-“Sportsman Hughes dies,” August 21, 1952

Afro-American (Baltimore)

– Herbert Frisby, “AFRO’s Frisby on Whale Hunt: Trip Marks Third Into Polar Area,” August 24, 1946. (Includes reference to Hughes as a prominent Prairie sports figure.)

Additional Material

– Biographical profile of Luther “Doc” Hughes by Ned Powers in 1996 Saskatchewan Historical Review by the Saskatchewan Baseball Hall of Fame

– Compiled timeline and research notes drawing on newspaper clippings from 1911–1952.